Throughout OEF’s journey, we have learned a few organizational heuristics that are key for embracing the characteristics of complexity while maintaining operational effectiveness and maximizing the opportunity for impact. We believe that one of the core competencies organizations can leverage in such contexts is how they learn and adapt–this is how we do it.

Calibrating for Complexity

Organizations like One Earth Future (OEF) are grappling with unprecedented levels of complexity in our rapidly changing world. Within this reality, we are collectively at risk of being ill equipped to deal with the ambiguity, novelty, and scale that such contexts present. As a result, building up our competencies for embracing and operating more effectively within complexity is becoming increasingly important. Better aligning our mindset, tools, and culture to the characteristics of complexity and how these change over time can enable us to approach problem-solving more intelligently and cost-efficiently. In turn, we can considerably reduce our work's vulnerability and maximize our impact within the existing constraints.

To this end, for over a decade, OEF has been on a journey of continual improvement seeking to operate as a complexity-conscious and adaptable organization. Throughout this experience, we have identified three key heuristics that help us stay aligned and effective in such dynamic, unpredictable, and complex contexts.

- Maintain a complexity-aware narrative. Narrative underlies everything any organization does. To avoid inaction and decision-making paralysis in complex contexts, we must resort to creating a simplified model of these contexts that we can more readily grasp and operate within. This forms a manageable, shared narrative that can inform planning, guide actions, and help determine what can be measured to evaluate progress. However, getting stuck in a narrative without intentionally and consistently updating it to better reflect emerging realities on the ground can result in several consequential outcomes:

- Decisions may be based on an erroneous understanding of the relationship between the work done and the changes observed in the context.

- Narrow stories of success based on select information can create false confidence in the effectiveness of our work.

- Opportunities for improvement may be missed.

- Changes in the context which affect underlying assumptions may be overlooked.

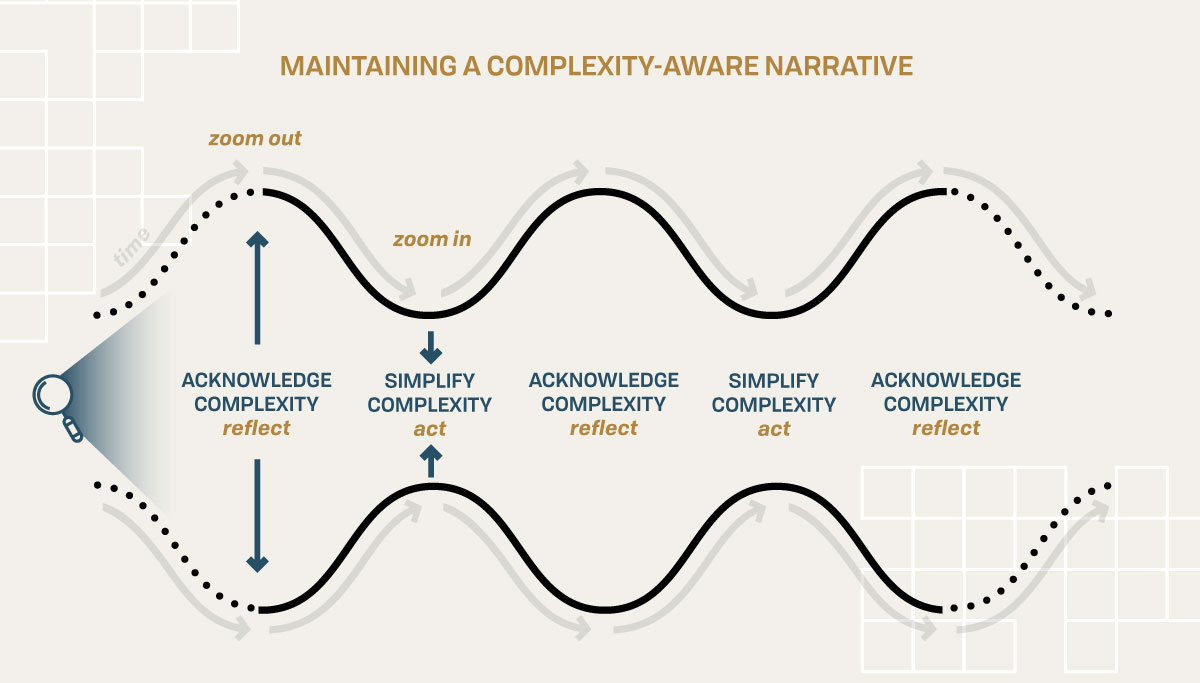

At OEF we believe we must intentionally engage in a consistent effort to maintain a complexity-aware narrative. This involves “zooming out” to acknowledge the complexity and see the big picture—the work and its results; stakeholder and context changes; trends and flags—and compare it to our current narrative reflected in our programmatic planning documents and the stories we tell ourselves and each other. It involves then “zooming back in,” and consciously re-simplifying that complexity into an updated narrative that can inform our next steps.

- Balance explicit data with tacit knowledge. Decisions made without data are flying blind. Yet data alone can be misleading since it provides only a narrow understanding of what is happening and limited insight into what to do next. There must be a balance between explicit data and tacit knowledge to help deepen evaluation and guide decision-making. When it comes to programmatic work this tacit knowledge is usually held by those doing the work “on the ground” who are closest to stakeholders. When weaved with data, individuals' experiential, elusive, intuitive knowledge can reveal critical insights.

- Codify what works, but remain open to it changing over time. If we want to maximize the impact we have per dollar and not be wasteful with the resources and time we have, we must be able to discern what works and what doesn’t. We also must be able to do more of what works (and, of course, stop what doesn’t). Both of these call for transforming “unknown knowns” into “known knowns.”1 This means arranging into concepts, words or systems that we understand but are not consciously aware of, and in so doing making it replicable. However, it is difficult to be successful with a fixed decision-making framework when confronted with complex contexts. Therefore we cannot blindly rely on our previous discoveries forever, shutting ourselves off from the very sources of input that led to those key realizations in the first place. Instead, we must remain adaptable and flexible, retaining inquisitiveness and humility in the face of an ever-changing reality. Our work must be informed by the intersection of “best practice” and the realities on the front lines of change.

The common thread among these heuristics is that their effective implementation relies on ongoing learning practices. As a result, in an effort to intentionally and systematically operationalize these heuristics into the fabric of OEF’s day-to-day, we combined them into a single process–The Learning Loop.

OEF’s Approach to Learning: “The Learning Loop”

We define “Learning” at OEF as systematically distilling knowledge from past and emerging experiences to establish guiding principles for future actions. Learning is a mechanism to demystify, make sense of, and optimize actions. Its ultimate aim is to achieve the intended impact in a more informed, cost-effective, and timely manner and to identify ways our approach must change to do so. The reality is that learning is always happening within teams as they navigate the day-to-day. However, it is often sporadic, not recorded, unorganized, and lacking intention. Unfortunately, it also tends to be an individual exercise that can result in important insights being overlooked or unexpressed.

At OEF, programs engage in a facilitated learning process called a Learning Loop. The process intentionally identifies gaps in knowledge about impact, seeks relevant insights about these gaps, attempts to add meaning to these insights, and integrates lessons learned through remedial action items. The Learning Loop uses M&E data as the basis for facilitation to ensure that conversations are rooted in empirical facets of reality. These reflection sessions also aim to uncover unexpected outcomes, gain insight into the correlation between the program’s actions and observed results, and codify what’s worked. Importantly, it engages the whole team to ensure a variety of voices contribute to the collective sensemaking effort. This process draws out diverse insights of the realities on the ground and the emerging impact of the program's work. These insights also provide feedback about how to update M&E frameworks and indicators, to ensure that reporting is based on relevant information. Moreover, impact evaluations benefit from a more profound understanding of what is actually unfolding.

The Learning Loop has four stages, outlined below.

INQUIRE

Narrowing the focus of learning to make it more effective. The process begins early in our program’s planning cycles. The ‘Inquire’ stage aims to draw out the critical gaps in programs’ knowledge that, if addressed, would provide the most value in their ability to achieve their outcomes. This inquiry process results in a program’s learning agenda, which is a list of prioritized learning questions to take through the learning process. These are questions that require a combination of data-derived insights and a collective sensemaking effort to address adequately. Each learning question is accompanied by a learning strategy—a plan of action to generate useful insights to help close the program’s identified knowledge gaps (eg. surveys, interviews, outcome harvesting workshops, sensemaking circles, research memos).

As an example, Secure Fisheries, an OEF program that promotes peace, economic stability, and resilience in Somali coastal communities through effective fisheries governance and management, identified the following knowledge gap to take through their quarterly learning loop:

- How can Secure Fisheries further enable communication and collaboration between the national government and the Co-Management Associations (CMA) created as part of programming to advance local resource governance, dispute resolution, and stakeholder collaboration?

- What actions the program and the CMA are taking that are most contributing to improving the dynamic between the national government and the CMA? What actions are most discouraging the dynamic between the national government and the CMA?

Addressing this knowledge gap would help the program identify, for example, what actions Secure Fisheries can perform to positively influence or improve the relationship between the national government and the CMAs.

SCAN

Monitoring beyond what we know we are looking for will yield a more holistic picture of reality and a less narrow understanding of impact. The scan phase focuses primarily on OEF’s Impact, Learning, & Accountability (ILA) team interpreting incoming M&E data, observing context changes, and gathering insights generated through the Learning Strategy. As new data enters the program's M&E trackers, ILA attempts to connect the dots, turning data into information and probing for insights that merit further exploration with the program team. These insights then become the basis of engagement with the program in the next stage.

A good example here is provided by PASO Colombia, an OEF program that facilitates sustainable peace in rural areas of the country by coordinating collaboration for economic development and social cohesion among farmers, rural communities, ex-combatants, government, and business. Operating from the basis of their learning agenda, which identified impact sustainability as a key area for improvement, analysis of data from PASO’s Annual Survey, economic productivity metrics, and local security conditions revealed significantly relevant correlations between the data points. Taking the time to map these metrics against one another unveiled a picture that was hidden when the indicators were seen independently. The insights derived from the data were taken into the next stage with the PASO team, who engaged in a process of reflection that led to key actions being taken.

DISCOVER

Turning new information into meaningful knowledge. This stage is about connecting the data-derived insights with the insights, intuitions, and experiences of the team on the ground. ILA facilitates “Sensemaking Circles”, where program teams openly reflect on data and make new connections to discern what is working and what is not. This discovery process results in a synthesis of insights, concrete implications, and actions for the team to carry into their future work.

As an example, Open Nuclear Network, an OEF program that uses open source data analysis and strategic engagement to reduce the risk that nuclear weapons are used in response to error, uncertainty or misdirection, conducted a Sensemaking Circle to reflect on how and why recent key outcomes were achieved. From this reflection, the team identified ways to improve the odds of future success. Vitally, they recognized how integration between expertise centers in the program was critical to achieving their desired impact.

INTEGRATE

Closing the loop on knowledge. The last stage of the process focuses on the application of what has been learned. The results from the learning process are now disseminated to relevant stakeholders and plugged into the program's operational workflows.

As an example, Shuraako, an OEF program that connects Somali region entrepreneurs to impact capital with the aim to foster economic growth, create jobs, and promote stability and peace, identified concrete remedial solutions to help substantially improve the efficiency of their loan model given emerging contextual challenges.

Learning is on-going and should not stop. Every iteration or new action could benefit from a formal learning process; there is always something to inquire, scan, discover, and integrate into a program’s existing knowledge. By engaging in ongoing learning, organizations can better align their theory of impact with their ability to deliver on it.

Our Learning Continues…

One Earth Future has the goal of actually addressing complex problems. As we said in our paper “Incubating Peace: One Earth Future’s Approach to Incubating and Scaling Programs for Sustainable Peace”, we take seriously, though not literally, the question “What would it take to solve this problem?” Inevitably, if we mean this then we also need to take learning seriously, since it holds the keys to discovering what actually works and what does not, and how to efficiently do more of what does.

What learning looks like and how it is executed will look different across organizations. The bottom line, however, is establishing a collective and consistent practice of reflection and iterative adaptation. By harnessing the collective knowledge of teams and stakeholders, we as organizations can dramatically improve our ability to optimize impact per dollar, maintain our competitive edge, and sustain the outcomes of our work in the face of the challenges that increasing complexity presents.

This is part one of a series on OEF’s learning journey written by OEF’s Impact, Learning, and Accountability team. Stay tuned for upcoming deep dives into the different stages of the learning process and more on what we’ve learned about learning. We’re always seeking to improve—please reach out to Aydin Shahidi ([email protected]) if you have any feedback or would like to connect about our learning process.

1 - The idea of known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns is derived from American psychologists Joseph Luft (1916–2014) and Harrington Ingham’s (1916–1995) analysis technique referred to as Johari window.

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights