The challenges of peacebuilding involve maximizing the contribution of multiple technical experts in an often quickly changing environment, and one where participants may not always trust all other participants or where they may be concerned about maintaining their individual authority to make decisions. OEF's Conor Seyle shares how a coordinated approach to peacebuilding can be most effective in these conditions.

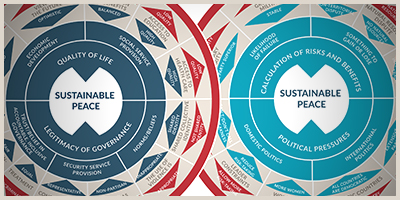

OEF’s work is focused on creating systems that will stop or prevent war and large-scale organized political violence. To do that, we have to have a theory of war - and peace - to help us strategize about where and how to work. Our understanding of conflict is that at the end of the day all wars are the result of multiple pressures and failures. That in turn means that peace is the result of multiple parallel pressures and interventions working in concert.

Believing strongly in our theory, based on documented evidence compiled through a decade of peacebuilding practice in the field, we also believe this poses a challenge to OEF, and to other organizations whose mission is centered on peace: It means peace can only be achieved by multiple different programs working on addressing security challenges, economic development, issues of inclusion and good governance, and social service provision simultaneously. More challenging still, all of these issues affect each other, and the actions taken by one program to address any of these issues can affect the plausibility or strategy of programs working on other issues. The scale of work needed, and the breadth of issues involved and the technical knowledge needed to address all of them, means that there are very few (if any) organizations out there that can, by themselves alone, meaningfully support societies in conflict or at risk of conflict in addressing the manifold domains that are needed. At the same time, the inter-connection between the issues means that without some form of coordination or collaboration between the different organizations working on addressing conflict, the risk is high that organizations working in one sphere may impact or be impacted by organizations working in another sphere, or that the community as a whole may miss something important and not realize it’s not covered.

Read More About OEF's Theory of Peace

This is a fairly well-known issue. Improving coordination across the different parts of the US government working on stabilization and peacebuilding is the core goal of the Global Fragility Act and associated Global Fragility Strategy. It’s been at the core of assessments of the UN peacekeeping architecture discussions. Despite that, there aren’t many good examples of such coordination: one academic suggested that the UN’s peacekeeping architecture was so uncoordinated that it should best be understood as “organized anarchy.”

OEF believes that one reason for this is a tendency either for collective peacebuilding responses to be loosely organized in an ad-hoc fashion (one version of the “organized anarchy” mentioned above), or instead for a reliance on hierarchy. Collective systems often gravitate towards some form of hierarchy, where there is some mechanism for developing a shared plan and enforcing the collective decision to execute that plan. Hierarchies are easy to understand, and they create the (occasionally illusionary) perception that the whole collective response is organized and acting in unison. They also create problems, though: by their nature it’s difficult to make sure that the collective plan reflects the different expertise of all the different technical areas involved - frequently they end up with one domain such as the military or the political driving the core plan, and other domains such as development are sidelined. In addition, it’s sometimes hard to get organizations to sign up for hierarchies, because it means surrendering their sovereignty to some collective plan.

OEF believes networks are an under-used solution to this. By networks, we don’t mean just collections of organizations or people who know each other - we don’t mean net work in the “social network” sense. Instead, we mean networks as an administrative structure. These are characterized by a lack of hierarchy. In a network, there is no authority and no formal way to force members to go along with some shared plan.

Instead, network structures operate by maximizing information flow about the different decisions and strategies of the actors involved. As long as all the participants really want to see the issue or problem resolved, the result is that the information about who’s doing what allows others in the network to identify places where their work is most useful, and for the network as a whole to identify issues and areas that might be under-served.

To some extent, OEF has to work this way: we’re an NGO, and we have little authority to set up new hierarchies in the areas where we work. And we don’t claim that networks are the one true answer in all situations - they are better in some ways than hierarchies, but they have their problems and strategic weaknesses as well. But we do believe that they are systemically under-utilized in the international peace and security system, and that they may be a particularly useful tool for peacebuilding.

The challenges of peacebuilding involve maximizing the contribution of multiple technical experts in an often quickly changing environment, and one where participants may not always trust all other participants or where they may be concerned about maintaining their individual authority to make decisions. In such conditions, networks shine.

In our work, OEF prioritizes supporting network structures for coordination. We do that at the program level as a tool for achieving our limited goals: PASO Colombia works in a network with local private sector, community, and government actors, for example, and Secure Fisheries is working to set up network systems around fisheries management in the Somali regions where they operate. We also strive to contribute, where we can, to setting up network systems at the level of the conflict as a whole because we know that is the level is where peace will be achieved.

Considering OEF’s strategy of peace as a whole, this theory of networks is the final piece in understanding our general thinking. Combined with our definition of peace and our theory of war and peace, this idea of network coordination provides an overview of our general thinking about how to develop our work. In future columns, we’ll dig more into our theory of operations - how we take this big-picture thinking and break it down to develop concrete strategies for ensuring our impact. OEF’s work is focused on creating systems that will stop or prevent war and large-scale organized political violence. To do that, we have to have a theory of war - and peace - to help us strategize about where and how to work. Our understanding of conflict is that at the end of the day all wars are the result of multiple pressures and failures. That in turn means that peace is the result of multiple parallel pressures and interventions working in concert.

Believing strongly in our theory, based on documented evidence compiled through a decade of peacebuilding practice in the field, we also believe this poses a challenge to OEF, and to other organizations whose mission is centered on peace: It means peace can only be achieved by multiple different programs working on addressing security challenges, economic development, issues of inclusion and good governance, and social service provision simultaneously. More challenging still, all of these issues affect each other, and the actions taken by one program to address any of these issues can affect the plausibility or strategy of programs working on other issues. The scale of work needed, and the breadth of issues involved and the technical knowledge needed to address all of them, means that there are very few (if any) organizations out there that can, by themselves alone, meaningfully support societies in conflict or at risk of conflict in addressing the manifold domains that are needed. At the same time, the inter-connection between the issues means that without some form of coordination or collaboration between the different organizations working on addressing conflict, the risk is high that organizations working in one sphere may impact or be impacted by organizations working in another sphere, or that the community as a whole may miss something important and not realize it’s not covered.

This is a fairly well-known issue. Improving coordination across the different parts of the US government working on stabilization and peacebuilding is the core goal of the Global Fragility Act and associated Global Fragility Strategy. It’s been at the core of assessments of the UN peacekeeping architecture discussions. Despite that, there aren’t many good examples of such coordination: one academic suggested that the UN’s peacekeeping architecture was so uncoordinated that it should best be understood as “organized anarchy.”

OEF believes that one reason for this is a tendency either for collective peacebuilding responses to be loosely organized in an ad-hoc fashion (one version of the “organized anarchy” mentioned above), or instead for a reliance on hierarchy. Collective systems often gravitate towards some form of hierarchy, where there is some mechanism for developing a shared plan and enforcing the collective decision to execute that plan. Hierarchies are easy to understand, and they create the (occasionally illusionary) perception that the whole collective response is organized and acting in unison. They also create problems, though: by their nature it’s difficult to make sure that the collective plan reflects the different expertise of all the different technical areas involved - frequently they end up with one domain such as the military or the political driving the core plan, and other domains such as development are sidelined. In addition, it’s sometimes hard to get organizations to sign up for hierarchies, because it means surrendering their sovereignty to some collective plan.

OEF believes networks are an under-used solution to this. By networks, we don’t mean just collections of organizations or people who know each other - we don’t mean net work in the “social network” sense. Instead, we mean networks as an administrative structure. These are characterized by a lack of hierarchy. In a network, there is no authority and no formal way to force members to go along with some shared plan.

Instead, network structures operate by maximizing information flow about the different decisions and strategies of the actors involved. As long as all the participants really want to see the issue or problem resolved, the result is that the information about who’s doing what allows others in the network to identify places where their work is most useful, and for the network as a whole to identify issues and areas that might be under-served.

To some extent, OEF has to work this way: we’re an NGO, and we have little authority to set up new hierarchies in the areas where we work. And we don’t claim that networks are the one true answer in all situations - they are better in some ways than hierarchies, but they have their problems and strategic weaknesses as well. But we do believe that they are systemically under-utilized in the international peace and security system, and that they may be a particularly useful tool for peacebuilding.

The challenges of peacebuilding involve maximizing the contribution of multiple technical experts in an often quickly changing environment, and one where participants may not always trust all other participants or where they may be concerned about maintaining their individual authority to make decisions. In such conditions, networks shine.

In our work, OEF prioritizes supporting network structures for coordination. We do that at the program level as a tool for achieving our limited goals: PASO Colombia works in a network with local private sector, community, and government actors, for example, and Secure Fisheries is working to set up network systems around fisheries management in the Somali regions where they operate. We also strive to contribute, where we can, to setting up network systems at the level of the conflict as a whole because we know that is the level is where peace will be achieved.

Considering OEF’s strategy of peace as a whole, this theory of networks is the final piece in understanding our general thinking. Combined with our definition of peace and our theory of war and peace, this idea of network coordination provides an overview of our general thinking about how to develop our work. In future columns, we’ll dig more into our theory of operations - how we take this big-picture thinking and break it down to develop concrete strategies for ensuring our impact.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights