Sexual exploitation and abuse flourish in situations of protracted conflict and post-conflict settings, even by those tasked to protect. UN Peacekeeping operations have come under fire of repeated reports of sexual misconduct- yet the UN has done little to hold them accountable. Our final post in the UN Peacekeeping series explores why, and recommends steps the UN can take.

In the past few years, UN peacekeeping operations have come under fire due to repeated reports of sexual misconduct of peacekeepers. A 2015 independent review of the peacekeeping operation in the Central African Republic traces an arc of sexual exploitation and abuse from the early deployments in Bosnia in the 1990s to the current UN mission in the Central African Republic.

“Exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers and personnel has been reported since the 1990s concerning peacekeeping missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, East Timor, Haiti, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan, among others.” —Human Rights Watch, 2016

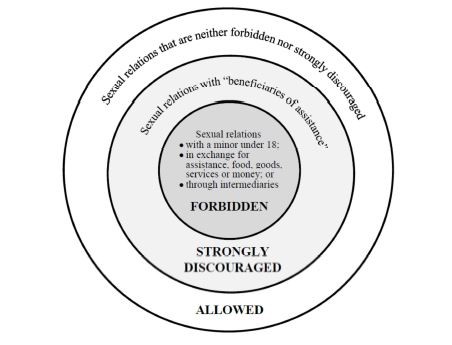

Sexual exploitation and abuse flourish and proliferate in situations of protracted conflict as well as post-conflict settings, which are often plagued by an absence of law and order. In addition, the UN has been slow to establish clear communication lines and mechanisms for victims. In 2003, then Secretary-General Kofi Annan released a bulletin that outlined rules on addressing sexual abuse and any sexual relationships in peacekeeping operations.

UN rules on addressing sexual exploitation and abuse. Adapted from Evaluation of the Enforcement and Remedial Assistance Efforts for Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by the United Nations and Related Personnel in Peacekeeping Operations, p. 7.

A comprehensive strategy—also known as the Zeid Report—to combat sexual exploitation and abuse followed in 2005. However, in a 2015 evaluation of efforts to address this problem in peacekeeping operations, the Office of Internal Oversight Services concluded that “the effectiveness of enforcement against sexual exploitation and abuse is hindered by a complex architecture, prolonged delays . . . and severely deficient victim assistance.”

Part of the problem is that peacekeeping operations depend on troop-contributing countries to commit personnel to conflict zones. In light of a constant shortage of troops, the UN holds little sway over the fighting forces that make up its missions. The authority over troops—including investigation and prosecution—stays with the country providing the troops, as is typically agreed upon in memorandums of understanding. This reduces the UN’s ability to hold peacekeepers accountable because complaints and allegations create a conflict of interest for the UN.

In response to the persistent instances of sexual exploitation and abuse committed with impunity by UN peacekeeping personnel, the Aids-Free World advocacy organization launched a campaign in 2015. Known as Code Blue, it has been trying to lobby for the establishment of a Special Court Mechanism that could prosecute both non-military and military UN mission staff. This proposal goes beyond the recommendations of evaluation reports by the UN, which suggest amending and revising existing contracts between troop-contributing countries and the UN.

Currently, UN personnel on foreign soil are protected under the cloak of the 1946 Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the UN. Military peacekeeping staff do not fall under this Convention but are “protected” due to the jurisprudence of their respective home countries as guaranteed in the MoU. As such, both the Convention and the respective MoUs provide a smokescreen behind which peacekeepers who exploit and abuse civilians can operate with relative impunity.

What can be done?

The UN has some leverage because it pays countries to contribute troops. In reality, though, the UN is too dependent on troops from countries with abysmal records of violence against women and children. What is needed is a strategy that addresses the attitudes of troops toward gender-based violence (such as mandatory pre-deployment gender training). The UN must also remove legal barriers to investigation and prosecution in these cases in peacekeeping missions. Lastly, the UN needs to invest in victim-centered approaches that would allow victims to come forward and receive necessary medial and psycho-social support.

Code Blue’s proposal for a Special Court Mechanism—to be approved and staffed by member states—is a first step to conceptualize better enforcement to combat this crime. It “would meet the needs of peacekeeping countries under siege and help to ensure impartial justice for victims, affected communities, and the accused.”

For previous pieces in this series and other analyses on international conflict and governance, check our ThinkPeace blog.

Article Details

Published

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights