Natural disasters affect more than the physical infrastructure in areas they hit. They also impact social and political dynamics. In situations of active armed conflict, this raises a question: can a disaster change the dynamics of conflict and provide an opportunity for peace?

One example comes from Indonesia. Within a year of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement signed a peace agreement, government troops pulled out of Aceh, and rebels disarmed, ending a decades-long separatist insurgency in the country. As many argue, the disaster strengthened political will toward peace and enabled successful negotiations (see here, here, and here).

Evidence shows that natural disasters do create ripe moments for conflict resolution by increasing the probability of cease fires and talks immediately after disasters. However, with few exceptions aside from Indonesia, they fail to produce long-term peace. In fact, disasters tend to prolong conflicts despite the initial cooperation that happens in a disaster's aftermath.

How can international actors reconcile these findings? Can they promote long-term peace in disaster-conflict contexts or will disaster-related cease fires and talks always be fleeting?

I argue that humanitarian actors and mediators can increase the odds of peace in disaster settings, but only when the conflict context is right. More rigorous and frequent conflict assessments are needed to recognize these moments. The assessments should focus on how disasters shape the incentives of the warring parties.

Disaster – an opportunity for peacemaking

Disasters can incentivize warring parties to cooperate by temporarily reducing their ability to fight, delegitimizing violence through increases in societal trust, and refocusing their attention on disaster relief. These changes in their incentives can result in various types of cooperation, from high-level negotiations to community-based rapprochement.

To support peacemaking, humanitarian actors and mediators can build upon this cooperation between warring parties that was initiated due to disaster response. In an ideal scenario, disaster-related technical collaboration, such as humanitarian cease fires, would lead to trust building, which in turn would lead to political dialogue and eventual conflict resolution.

To support this process, organizations already working with warring parties can advocate for 1) extending cease fires to facilitate reconstruction efforts, 2) formalizing short-term humanitarian arrangements, such as aid delivery routes, so that they last after immediate disaster relief has concluded, 3) drafting joint statements on disaster recovery and disaster risk reduction plans, and 4) facilitating new talks, depending on the stage of the peace process prior to the disaster. However, while such actions can pave the way to conflict resolution, their success is not guaranteed.

Disaster – an opportunity for conflict escalation

Warring parties tend to also take advantage of a temporary lull in fighting and rapprochement following disasters to escalate the conflict. Armed groups can increase recruitment among disaster-affected populations and loot humanitarian aid to strengthen their resource base. Governments, in turn, can use disaster response as a guise for counterinsurgency efforts by deploying military in affected areas. Both can engage in temporary cease fires and talks to buy time to re-arm and build legitimacy.

When either or both see an opportunity to escalate and win the war, technical cooperation for peacebuilding will be futile. In fact, humanitarian efforts to bring warring parties together can significantly hurt peace prospects.

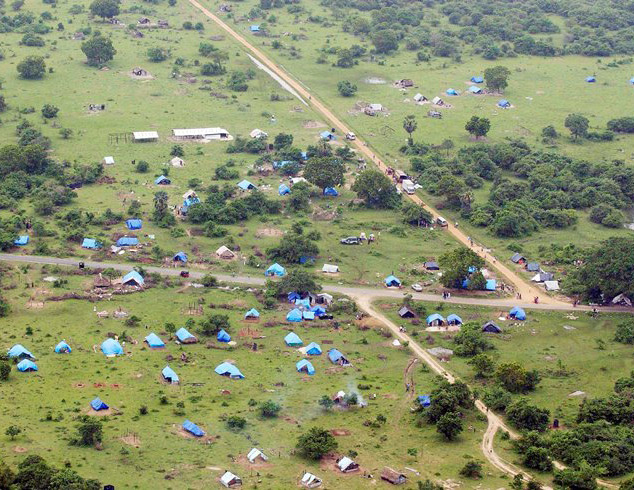

The example of Sri Lanka after the Indian Ocean tsunami demonstrates that. Pressure from international donors resulted in the creation of a joint aid mechanism (P-TOMS) between the government of Sri Lanka and Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. However, neither of the parties sought peace and continued to perceive winning the war as a viable option. As a result, P-TOMS was marred in political controversy and became a key stumbling block in the peace process.

One of the broader initiatives to use technical cooperation for peacemaking, the World Health Organization’s Health as a Bridge for Peace policy, also shows the importance of conflict context in such work. The program’s goal was to provide health services, such as immunizations, while also advancing peace between warring parties. USAID’s evaluation of the program stressed that it was only successful when the programs were “tailored to specific contextual situations” and when there was “political will of national governments”.

Conflict context matters for peacebuilding, especially after natural disasters

Most humanitarian and development organizations working in conflict zones already do extensive conflict analysis to ensure their operations do not aggravate violence. However, the analysis is often done at the beginning of program planning and is not adjusted following external shocks, such as natural disasters.

This is a sub-optimal approach, given that the conflict context changes significantly once a disaster strikes. We know that disasters change the incentives of the warring parties by affecting their mobilization capacity, priorities, and available strategies. As mentioned above, the combination of these factors can provide ample opportunities for both cooperation and escalation.

Humanitarian and peacebuilding actors should assess these dynamics once a disaster strikes if they hope to use disaster response to jump-start conflict resolution.

Humanitarian and peacebuilding actors should assess these dynamics once a disaster strikes if they hope to use disaster response to jump-start conflict resolution.

How can we figure out if the context is “right”?

To do that, humanitarians, mediators, and other peacebuilding and peacemaking actors can ask the following questions as part of conflict assessments:

- Were food, water, infrastructure, and other resources needed for mobilization affected?

- How fast can the parties replenish them?

- Can the parties recruit in disaster-affected regions?

- Do the parties need each other’s cooperation to deliver aid?

- Do they depend on disaster response for their legitimacy? (i.e. extremist groups rely less on the population’s support).

- Have the parties expressed interest in a peace settlement?

- Were the parties engaged in negotiations or a cease fire prior to the disaster?

These questions stem from all the different mechanisms in which a disaster can motivate parties to cooperate or escalate, discussed above. All in all, they must help international actors answer the following question: does each warring party perceive its ability to win as waning and negotiations as a good alternative?

For example, if the rebels no longer have access to ample food, water, and recruitment, depend on disaster response for civilian support, and have expressed willingness to negotiate prior to the disaster, technical cooperation as a peacemaking measure will have a better chance of being successful.

On the contrary, if the disaster wiped out the capital city or key government resources, but hardly affected the rebels and their mobilization capacity, genuine interest in resolution is unlikely: the rebels are likely to believe they can win and escalate their attacks on the weakened state.

Concluding thoughts

The fact that conflict context is key to any international peacemaking intervention is hardly a new idea. However, evidence suggests that post-disaster settings do provide unique opportunities for conflict transformation in terms of both conflict resolution and escalation.

The lack of understanding of these dynamics might be the reason why we do not see more sustained conflict resolution outcomes after disasters. Humanitarians, mediators, and other international actors working with warring parties might be missing out on opportunities for collaboration and trust-building.

Increasing the rigor and frequency of conflict assessments is the first step towards recognizing these opportunities and acting on them to promote peace in post-disaster contexts.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights