A look at the role of urban centers versus rural areas as an interesting yet often overlooked element in research on intrastate conflict.

Presidential elections in Colombia matter a lot for the peace agreement between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the national government. The agreement has been the source of contentious political debate with some leading candidates for the presidency in fierce opposition to the agreement.

As is often the case for national elections, regional differences are center to national political dynamics. The dynamics between urban areas and rural areas in Colombia are particularly interesting. Much of the FARC’s violence was concentrated in rural areas, and this was in part reflected in the failed October 2016 referendum on the peace agreement with the FARC.

But, Colombia has become increasingly urban since the conflict began, “mainly because of the greater security provided by increased distance from the original place of violence and the anonymity of a large city.” This displacement created a sharp increase in the urban populations of the country’s largest cities, including Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali.

Yet, Colombia’s cities are by no means immune to violence. Between armed groups, drug cartels, and other illicit activities, Colombia’s cities have dealt with their own forms of violence and insecurity in the context of a larger intrastate conflict.

The role of cities is an interesting yet often overlooked element in research on intrastate conflict. Many scholars have considered the impact of conflict on cities, but the opposite causality hasn’t been explored as much. OEF Research has developed some work suggesting that cities are increasingly powerful in this space, and in some cases, cities may have a significant role to play in conflict mitigation. How cities interact within a given political context and within intrastate conflict can also bear significant influence on the outcomes of national elections.

Medellín: Contested Space and Role Model

Medellín, located in the Antioquia department, is a prime example of how a city can shape outcomes for peace and security. Medellín was known as one of the most violent cities in the world in the 1980s and 1990s, with a murder rate peaking in 1991 at 381 per 100,000 residents. In 2017, the murder rate dropped to 22 per 100,000 residents (for reference, Chicago has a slightly higher rate at 23.8).

This drop in violent crime is partially credited to the city’s efforts to reintegrate former combatants. “The first big block of paramilitary demobilizations” took place in Medellín beginning in 2002. The city government took a more proactive approach to reintegrating former combatants by providing psychological counseling, building public transportation to and from the cities’ poorest districts, and dedicating 40 percent of the city’s spending to education.

Much of this work is attributed to a series of innovative mayors who governed Medellín at the time. For example, Sergio Fajardo was mayor of Medellín between 2004 and 2007. A New York Times article dubbed him “Medellín’s Nonconformist Mayor” for his work on public infrastructure, education, and violence prevention programs. Fajardo was also one of the candidates running for president, coming in third with 23.4 percent of the vote.

Yet, despite this experience and relatively successful reintegration model in Medellín, the city’s political culture veers conservative, not because they don’t want peace but because they think the agreement is too lenient on the FARC. The Antioquia department largely rejected the 2016 peace agreement referendum by 62 percent (no) to 38 percent (yes).

Rural-Urban Divide

Much has been written about the reasons the referendum failed in 2016. Commentary at the time focused on urban and rural voting dynamics as one reason. For example, Splinter News interviewed residents of one rural community that had directly experienced FARC violence following the failed referendum:

“We feel like we have been abandoned,” said Leyner Palacios, a human-rights activist in the remote jungle town of Bojaya. “The accords were good for the countryside, so for urban Colombia to deny us this possibility is almost like telling us we are not Colombians.”

There is some support for this claim in political science literature. Namely, threat perception is a key factor in peace and security that determines how states, or countries, identify and prioritize different threats to power. Geographic proximity is one element that suggests threats closer to the “state” pose a greater danger. When applied to conflict dynamics within the state, it suggests that the closer an urban population is to a conflict, the more immediately threatening the conflict appears.

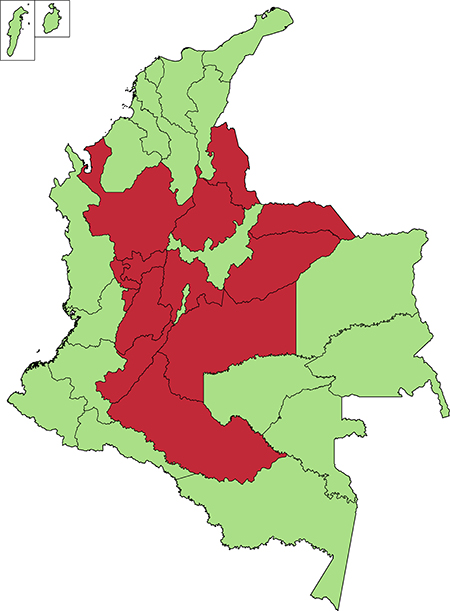

This played out in some fashion during the October 2016 referendum on the Colombian peace agreement with the FARC. Those opposed to the agreement were concentrated in urban areas (red), with the exception of Bogotá, while those in favor of the agreement where located mostly in rural areas (green).

Image from Wikipedia

Formally ending the conflict with the FARC seemed to be of greater concern for the rural populations who had been disproportionately affected by the violence. The rejection of the agreement in urban centers, which was primarily based on fears the FARC would get away with impunity, is a prime example of the historical divide between urban elites and rural populations in Colombia.

Looking Backward, Moving Forward

The 2016 referendum displayed the contrast between the urban power centers and the neglected rural areas. This underscores the tense political dynamics within Colombia. Political and economic elites in cities certainly have less to gain from an agreement that focuses on rural development, grants the FARC access to Colombian politics, and includes reparations for all victims. Attempts to redistribute wealth to rural communities and ex-combatants is an unpopular way to communicate peacebuilding efforts to urban elites who have been largely removed from violence.

Medellín’s rejection of the referendum is particularly interesting given the investments in reintegration programs and social inclusion initiatives. Marginalized and formerly violent neighborhoods have gained back public space, but the wounds left by the conflict run deep. This, in turn, continues to impact voting behavior, which will continue to impact elections in Colombia and future support for the peace agreement.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights