During the five-month siege of Marawi City in the southern Philippines, security actors also engaged with nearby fishing villages in Lake Lanao to facilitate a security response.

by Rosalie Arcala Hall, Ph.D.*

In May 2017, ISIS-linked terrorists comprising the Maute armed group and based in Lanao del Sur province, along with the Sulu-island–based Abu Sayyaf Group led by Isnilon Hapilon, laid siege to the city of Marawi in the southern Philippines. The five-month conflict killed 114 civilians and 168 government troops and left the city’s commercial core, dubbed the Main Battle Area, in ruins. By October 2017, the conflict had displaced 353,921 residents in Marawi City and other towns located near Lake Lanao. During this conflict, culturally sensitive and mediated interactions between security forces and fishing communities were key to protecting the lives of fishermen while facilitating a successful security response.

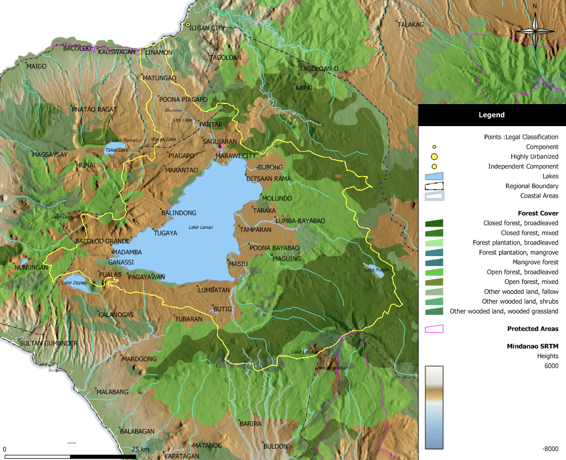

Lake Lanao is a major transport route and source of fish and shellfish for local consumption, and the reservoir for Agus dam, which supplies 60 percent of Mindanao’s electricity. Decades of separatist conflict, weak watershed management institutions, and lack of fisheries law enforcement have led to a serious decline in fisheries production and loss of endemic species. The lake is also used as a highway for moving drugs and contraband by anti-government non-state armed groups such as the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the New People's Army.

Lake Lanao became a crucial extension of the main combat effort at Marawi. Understanding the lake’s strategic importance, the government employed a Joint Task Group (JTG), dubbed JTG Lawa, featuring composite army, naval, coast guard, and maritime police personnel to patrol the lake. From a security standpoint, the JTG patrols succeeded in preventing casualties among fishermen and repelled several attempts by the terrorists to escape via the lake. However, the JTG’s impact on fishers’ economic livelihoods was mixed. As fishing and mobility around the lake were restricted, the incomes of fishing households were reduced. Only in some localities, where local government units agreed to compensation for fishers, were the adverse effects mitigated. Overall, fishers became more organized and their activities better regulated by the state as a result of security measures.

The armed campaign featured air, ground, and naval operations, with security measures to prevent reinforcement of supplies and escape of the terrorists. Naval operations in Lake Lanao included restrictions on fishing and transport by vessel. Ground operations restricting entry into and out of Marawi City, called the Controlled Area, blocked the flow of humanitarian aid and commercial goods to towns around the lake, causing further displacement.

The armed campaign featured air, ground, and naval operations, with security measures to prevent reinforcement of supplies and escape of the terrorists. Naval operations in Lake Lanao included restrictions on fishing and transport by vessel. Ground operations restricting entry into and out of Marawi City, called the Controlled Area, blocked the flow of humanitarian aid and commercial goods to towns around the lake, causing further displacement.

The JTG Lawa positioned tanks along the nearby shorelines to prevent the escape of the terrorist groups. Waterborne patrols and blocking operations were carried out in the lake’s northern section while infantry units were deployed in ports and town checkpoints. JTG Lawa units administered and monitored ferries and fishing vessels while local police and volunteers augmented surveillance and patrols.

Of the 15 littoral towns around Lake Lanao, the northern towns (Subong, Ditsaan Ramain, Malundo, Taraya, Tamparan, Marantao, Balindong, and Tugaya) were the focus of JTG Lawa regulatory operations. Restriction on fishing activities included confinement to nighttime fishing below the fireline and the use of non-motorized boats only. Owners were required to register their boats with the military and operators were given IDs. Boats were marked with numbers corresponding to the military database and were checked at ports and landings if they went into the lake. Boats that violated security rules were confiscated and impounded.

Although the imposition of martial law throughout Mindanao legalized the military’s enforcement task, it nevertheless had to engage locals to make them comply with the security measures. Adopting a civil–military operations framework, JTG Lawa officers held dialogues with the local government unit and fisherfolk groups. During these meetings, officers explained limits on fishing activities and ferry operations and rules regarding boat registration, checks and confiscation, and they asked that fishers not bring motorboats to the lake. The dialogues also became platforms for negotiations; for example, shrimp fishers in Tugaya requested a limited 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. window for fishing. Because military personnel were not local, they used interlocutors (imams, religious leaders, elders, the mayor, and village leaders) as conduits for obtaining local cooperation. In addition, the officers were able to convince some mayors (e.g., those of Balindong and Masiu) to provide cash-for-work opportunities or extend monetary assistance to those fishers adversely affected by security operations. JTG Lawa also used its assets and personnel to distribute proceeds from the government’s conditional cash-transfer program to beneficiaries around the lake towns.

Although the imposition of martial law throughout Mindanao legalized the military’s enforcement task, it nevertheless had to engage locals to make them comply with the security measures. Adopting a civil–military operations framework, JTG Lawa officers held dialogues with the local government unit and fisherfolk groups. During these meetings, officers explained limits on fishing activities and ferry operations and rules regarding boat registration, checks and confiscation, and they asked that fishers not bring motorboats to the lake. The dialogues also became platforms for negotiations; for example, shrimp fishers in Tugaya requested a limited 4 a.m. to 6 a.m. window for fishing. Because military personnel were not local, they used interlocutors (imams, religious leaders, elders, the mayor, and village leaders) as conduits for obtaining local cooperation. In addition, the officers were able to convince some mayors (e.g., those of Balindong and Masiu) to provide cash-for-work opportunities or extend monetary assistance to those fishers adversely affected by security operations. JTG Lawa also used its assets and personnel to distribute proceeds from the government’s conditional cash-transfer program to beneficiaries around the lake towns.

The activities of JTG Lawa featured the staple “stakeholder engagement” which is now institutionalised in the Philippine military. Under this doctrine, the military is tasked with mounting dialogues and negotiating with communities on security measures, and being culturally sensitive by adopting locally prescribed mechanisms. The officers also coordinated with linchpins in positions of power, notably the mayors whose control over local police and fiscal resources were vital for security missions. At the beginning, earning the support of the mayors was difficult because prior land-based operations against the ISIS-linked terrorists had resulted in displacements. Cooperation required reciprocal gestures to build trust, with the local government units providing billeting and space for command posts and extending logistical assistance. Ultimately, only two of the 15 mayors worked with the military to engage the fishers.

While the JTG Lawa operations protected the lives of fishermen and repelled a planned terrorist attack, they also affected fishing livelihoods around Lake Lanao. Restrictions on access to fishing grounds resulted in loss of income. Inherent weaknesses in the local government apparatus meant that only some localities provided income augmentation measures. Military–fisher engagement, although premised on sound cultural approaches, was securitized and was mediated by community opposition to martial law and the primacy of the military mission to subdue the terrorists in Marawi. On the other hand, the mandatory boat registration and the resulting fishing database, while intended for surveillance, helped bring a level of organizational formality and local regulation.

The experience in Marawi portends the possibilities for military units working with local government officials and fishing communities towards common security goals that are sensitive to the fragile economic conditions of fishers. The military as an agent of the state can be instrumental in building trust towards formal institutions and giving fisherfolk access to government resources. The war may be over in Marawi, but residual security concerns put a premium on more dialogues between uniformed personnel and civilians on how best to address conflicts.

Image captions:

1- Lake Lanao as seen from the Mindanao State University-Marawi City campus. Photo credit R. A. Hall.

2 - View of Lake Lanao from the Main Battle Area of Marawi City. Photo credit R. A. Hall.

*Dr. Rosalie Arcala Hall is a Professor of Political Science at the University of the Philippines Visayas.

Footnote: Data for this post was derived from the Australian National University (ANU) Philippines Project Collaborative Grant “Complex Emergency: Engagement between Civil Society Groups and the Philippine Military during the 2017 Marawi Siege,” for which the author is Principal Investigator. The study involved 49 interviews of national, provincial, and city/municipal officials, civil society organizations, and military and police officers from April to September 2018. Proceedings from three focus group discussions with police officers and Bureau of Fire search-and-rescue teams were also included.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights