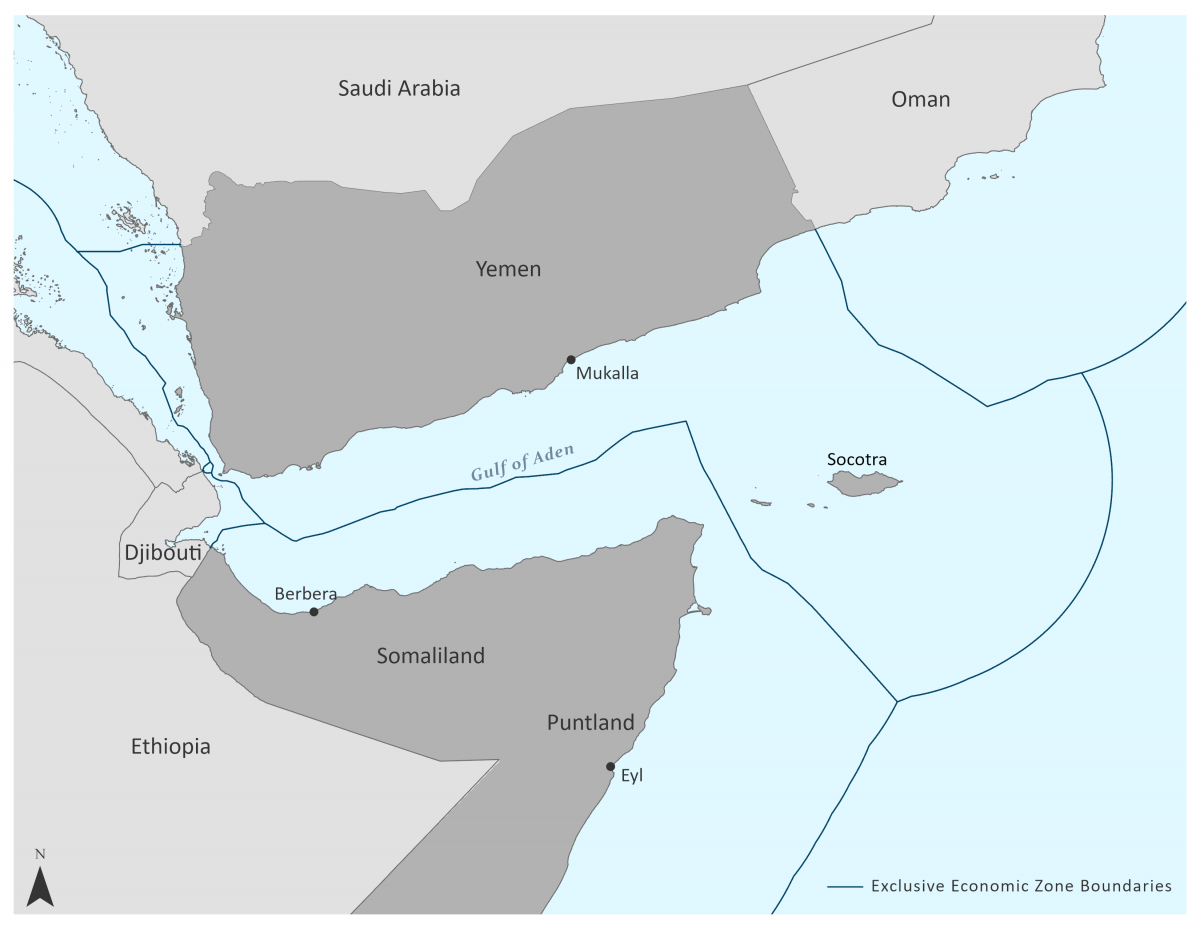

Fisheries conflict in Somali waters has impacted people from dozens of countries, but no foreigner has been as involved and affected as the Yemeni fisher. From 2006 to 2010, the spiraling consequences of overfished and unmanaged Somali fisheries resources spread into Yemen’s waters, putting its domestic fishers at risk of attack from pirates and warships, alike.

This case study demonstrates how informal peace agreements can begin to unravel in the context of resource scarcity.1

Onshore demand for fisheries products and high trading potential have increased Yemen’s interest in its maritime space since the 1970s. Informal agreements that were developed between Yemenis and Somalis starting in the 1990s allowed all fishers to travel the waters freely. Yemenis would bring fuel, and eventually ice (subsidized in Yemen), in exchange for access to Somali fishing grounds or fish purchased directly from Somali fishers at low prices.

What was once a peaceful, mutually beneficial relationship between Yemeni and Somali fishers became unstable as competition over fishing grounds escalated. A brutal civil war in Somalia decimated infrastructure and left their resource-rich coastal waters undefended. Distant-water fleets took advantage of the anarchy in the region by fishing throughout Somali waters without licenses and without benefit to Somalis. Though high-efficiency gear, like purse seines and commercial trawls, caused the most environmental damage, the artisanal Yemeni vessels were blamed by Somali fishing communities and governments for declining fish populations.

Conflict grew most intense in Somaliland and Puntland, where the state governments were formalizing their maritime authority. When piracy was rampant in the Gulf of Aden (2008–2012), Yemeni fishing vessels were targeted by organized pirate groups, increasingly controlled by criminal gangs motivated by ransom opportunities. Hijacked fishing vessels were commonly used by pirates as motherships to carry out attacks far out at sea. Quests for profit drove piracy to grow beyond something the Somali region could extinguish alone. The Somali government’s plea for assistance brought foreign naval warship coalitions into the region. Somali and Yemeni fishers alike alleged that the harassment they endured from pirates multiplied with the arrival of foreign warships, who confused their fishing vessels for pirates’. Many Yemeni fishers decided to remain close to their beaches to not fall victim to mistaken identity.

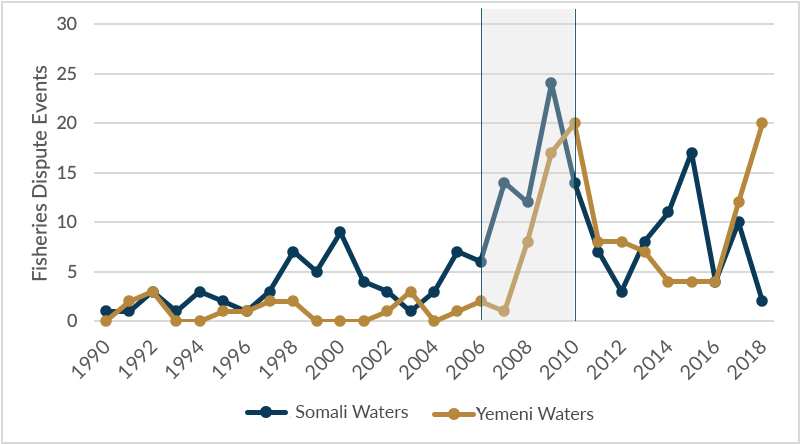

Figure 1. Fisheries Dispute Events in Somali and Yemeni Waters, 1990–2018.

The time period covered in this report (2006–2010) is indicated by the shaded area.

2006: Early Threats to the Peaceful Yemeni-Somali Trade Agreement

-

The Somaliland Coast Guard arrested Yemeni fishers and seized eight boats as part of a campaign to enforce territorial sovereignty in the Gulf of Aden.2 Yemen reported the event as a pirate attack.3

-

Somali pirates abducted 50 Yemeni fishers on four vessels while they were carrying out fishing activities on the coast of Abdul Kori Island, Socotra.4

2007: Puntland Increases Control over Its Waters

-

Puntland began formalizing the processes by which Yemenis could fish in its waters. Using an agent in Yemen, fishers could buy licenses that allowed them either to buy fish directly from Somali fishers or to fish in the waters of Puntland. The license included provision of an onboard armed guard to protect the crew from pirate attacks. Before reaching the Puntland coast, Yemeni fishers risked encountering pirates who would stop their boats and seize the fishers’ diesel and food. Sometimes the pirates kidnapped them and demanded $20,000 for their release. Some Yemeni fishers tried to outrun the pirates, but fishing in Somali waters was their only way to earn a living. The leader of the Fishery Cooperative Union in Mukalla, the umbrella organization for fisherfolk in Yemen’s Hadramaut state, advised fishers not to go on individual fishing trips into Somali waters.5

-

The Transitional Federal Government, the acting national authority in Somalia at the time, warned Puntland not to make deals over its territorial waters with other federal governments.6

-

Puntland complained that illegal Yemeni fishing vessels played a large role in depleting fish stocks in their waters.7 As a part of their crackdown on illegal fishing, Puntland security officials seized 130 Yemeni fishers in nine dhows for illegally fishing in Puntland’s waters.8

2008: Pirate Activity Increases and Foreign Warships Arrive

-

Reports of harassment against Yemeni fishers escalated in 2008. Yemeni media reported about 50 fishing boats had been attacked by pirates, resulting in over 70 fishers held hostage.9

-

Somali pirates hijacked a fishing boat and used it as an attacking ship, placing their Yemeni hostages as decoys.10

2009: Yemeni Fishing Decreases as Violence Escalates

-

Pirates continued to harass fishers, making the fishers not only victims but pawns in pirates’ deadly quest for profit. Yemeni fishers in Somali territorial waters were fired upon, held as hostages, used as human shields during attacks, and killed by pirates for something as insignificant as an engine.11

-

Foreign warships, as part of the international counter-piracy operations in the region, began targeting Yemeni fishers, mistaking them for pirates.12

-

The Somaliland Coastal Guard arrested 81 Yemenis in six fishing boats near Berbera (northern coast) for unlicensed fishing. The commander of the Somaliland Coastal Guard said their forces doubled their efforts to combat illegal fishing.13

-

An official report by the Yemeni government linked piracy to a US$200 million loss to its fishing industry, as Yemeni fishers stopped fishing even in their own waters out of fear of pirate attacks and being mistaken for pirates by international defense forces.14

2010: Nowhere to Fish and No One to Help

-

Fishing boats from Oman and Yemen that used to sail to Eyl (Puntland) to buy fish and trade goods no longer arrived because foreign warships were looting and destroying their boats.15

-

Three Yemeni fishermen were kidnapped by a gang of pirates that assaulted them and threw them into the Gulf of Aden. They were found alive on a Yemeni beach three days later. This story caused most Yemeni fishers to be too afraid to travel more than 20 miles offshore. They said their business was cut in half. They also felt their lives were threatened by international forces patrolling the waters.16

-

Though Yemeni fishers ceased straying far from shore, piracy reached them in their own territory with multiple incidents well within Yemeni waters,17 including the island of Socotra, an important Yemeni fishing ground.18

-

Fed up with continued abuse and harassment by foreign naval armadas, including violence and theft, Yemeni fishers held a sit-in demonstration in Mukalla. They claimed the forces in the region are often as dangerous as the pirates themselves.19

Somali piracy reached its peak in 2011, and the indirect economic consequences of the violence were felt by Somalis unable to trade with their former partners and by Yemenis who were left with nowhere to fish in peace. The controversial presence of international navies likely served its stated purpose, as the frequency of fisheries conflict in the region dropped dramatically by 2012 (Figure 1). Yemeni fishers had only a brief reprieve from conflict, however, as piracy was replaced by civil war. The Yemeni Revolution began in 2011, setting off a chain of events that would lead to the Yemen Civil War. By 2015, Yemeni fishing communities were under attack by land, sea, and sky, preventing them from fishing in their own waters or beyond—once again, scapegoats in someone else’s fight.

References

- This piece expands upon some of the research presented in Secure Fisheries’ Rough Seas: The Causes and Consequences of Fisheries Conflict in Somali Waters report.

- “International Affairs,” PAP Newswire, March 31, 2006.

- “U.S. Navy, Suspected Pirates Clash,” CNN.com, March 18, 2006.

- “50 Yemeni Fishermen Abducted by Somali Pirates: Official,” Agence France-Presse, March 7, 2006.

- “Yemenis Take Big Risks Fishing in Waters,” Africanews, September 19, 2007.

- “Govt. Demands Return of Six Ships,” Africanews, July 3, 2007.

- “Yemenis Take Big Risks Fishing in Waters.”

- “Puntland Releases Yemeni Fishermen,” Africanews, May 10, 2007.

- Ahmed Al-Haj, “Big Mistake: Pirates Caught after Attacking German Naval Ship off Somalia,” Canadian Press, March 30, 2009; “French Navy Prevents Pirate Attack off Somali Coast,” Deutsche Presse-Agentur, January 2, 2009; “Yemen Charges 22 Somalis with Piracy in Gulf of Aden,” Deutsche Presse-Agentur, July 15, 2009; “Kenya Charges Somali Pirates,” Agence France-Presse, November 19, 2008.

- Laura Kasinof, “Yemen’s Fishermen Caught between Somali Pirates and Pirate Hunters,” Christian Science Monitor, June 17, 2009.

- “Piracy Threatens Fishermen in Yemen,” Colombo Times, November 28, 2009.

- “Somalia: Livelihoods—and Lives—at Risk in Puntland,” Africanews, August 24, 2009; “Yemen’s Fishermen Caught between Somali Pirates and Pirate Hunters.”

- “Eighty-One Yemenis Deported from Northwest Somalia for Illegal Fishing,” Xinhua News Agency, February 6, 2009.

- Alyssa Rallis, “Yemen Lost $350US Mil. to Piracy, Says Report,” IHS Global Insight, July 17, 2009.

- “Somali Fishermen in Danger Due to Illegal Fishing,” BBC Monitoring Africa, January 27, 2010.

- “Pirates Threaten Lives and Livelihoods of Yemeni Fishermen,” Thai News Service, March 1, 2010.

- “Yemeni Man Gets Life in Prison for Piracy,” Associated Press, October 21, 2011.

- “Pirates Hijack Fishing Boat,” Edmonton Journal, May 8, 2010.

- “Anti-piracy Forces off Yemen Playing Pirates with Fishermen,” Arab News, May 6, 2010.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights