This “Empirically Speaking” column explores the ways that collaboration and coordination can act as drivers of trust in local government and data from OEF's PASO Colombia program that shows a meaningful correlation.

What makes an institution legitimate?

While political theorists have debated that question for several hundred years from the question of first principles, for most people’s lived experiences there’s a more straightforward answer: legitimate institutions are the ones seen as legitimate—the ones endowed by history, culture, or law or simply trusted by society to be the arbiter of disputes. From that perspective, the issue of trust is critical—regardless of how well an institution performs, if it loses the trust of its citizens, then its legitimacy is challenged.

From the perspective of peace, this dynamic is pivotal because the trust and legitimacy that people place in institutions play a major role in preventing citizens from choosing to use violence to resolve disputes. Because of this, OEF tracks changes in participants’ trust in institutions as a part of understanding the impact of some of our programs, including our work in Colombia through PASO Colombia.

While the last two years have been challenging for the whole world, 2020 was a particularly rough year for Colombians, who experienced significant popular unrest and violence. Though violence in the country decreased temporarily after the signing of the historic peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 2016, it has been gradually increasing in recent years. In 2021, the threat of violence from armed groups resulted in 73,974 people being forced to leave their homes, almost doubling the amount from the year before. The second year of the pandemic saw 255 people killed in 66 massacres, including 120 human rights defenders, many of whom were operating in rural areas. Public manifestations that broke out in urban areas in response to police brutality were responded to harshly by the government, which resulted in 13 deaths and hundreds injured. Our own surveys demonstrated that trust in government and governmental institutions took a hard hit due to these events, with on average 37% of our sample in the three most-affected areas reporting worsening trust in the national government, 41% reporting decreased trust in the army, and 49% reporting decreased trust in police.

Within this turbulent context, our program PASO Colombia, continued its five-year track of supporting rural economic and social development through collaborative productive projects in ERAs (which stands for Rural Alternative Schools in its native Spanish).

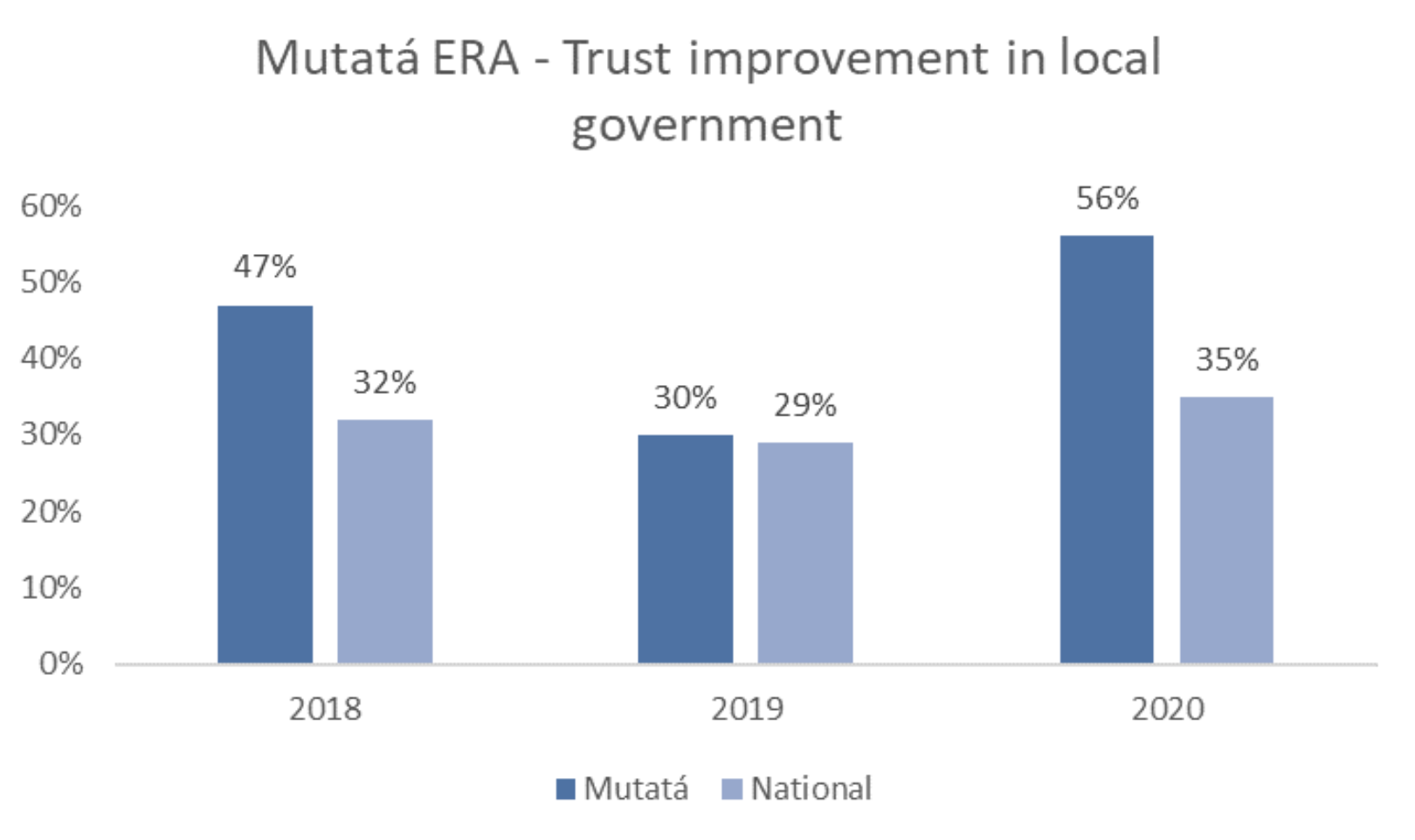

Despite the turmoil experienced in the country and the significant fall in trust in the national government, PASO’s annual survey conducted on ERA participants showed historic highs in the dimension of trust in local government.

The contrast of this data with the negative results associated with the national government and what we saw in the rest of the country was intriguing, to say the least. We sought to understand why these opposing results emerged and how they could be made sense of in relation to PASO’s work.

In part, the difference in the trust data can be attributed to the focus of the nationwide protests. They were primarily focused in urban areas, while ERAs are virtually all in rural areas. The protests were also focused on the national government and the institutions associated most directly with it (i.e. police, military, ministries).

Rural populations, including ERA survey participants, likely witnessed the protest events second-hand through media reports, social media, and accounts from others who were directly exposed. Therefore, their trust sentiments may have been influenced by these factors. Despite not being directly affected, whatever negative sentiments of the national government existed in the past may have been brought to the surface.

The differences in trust in local versus national institutions may also in part reflect the psychological dynamics of crises or disasters or other situations when people feel threatened. The aphorism that “all politics is local” becomes particularly true when people feel under threat. When risk or threat feels personal, people tend to focus more on local social networks and emphasize their immediate environment, including local institutions.

ERA participants were and are directly affected by the local rural government institutions. In this regard, their involvement in the ERA may have contributed to them having positive experiences with local institutions which directly benefited them. This potential outcome is by design—PASO’s ERA model, at its core, is one of networked coordination. Rather than provide an out-of-the-box “solution,” it partners with local stakeholders to understand their needs and problems. Then, PASO finds partners that fill the gaps and facilitates the relationships needed to fix problems. All ERAs weave together the partners and resources that can bring about social and economic development and territorial cohesion: education and training, access to land and credit, organizational strengthening, and commercial partnerships. Local government is an integral part of this weave; they tend to provide vital support, such as infrastructure, and can serve as an integrator with the broader community and other government agencies.

ERA Vignette: Mutatá

For example, in 2017, a group of 50 ex-combatants left the Territorial Training and Reincorporation Space of Tierralta, Córdoba in search of better economic and livelihood opportunities for themselves and their families. Even though the peace agreement between the Government of Colombia and the FARC guerrilla was signed a year before, the economic components of the reincorporation process in Tierralta were stuck. Little to no progress had been made in terms of what was agreed to: productive projects, access to land, housing, and basic social services. A feeling of frustration started to emerge within the group. With their combined reincorporation stipends, the ex-combatants purchased 21 hectares of land in the San José del León hamlet in the municipality of Mutatá. They then brought their children, livestock, and some belongings with them, and started building their new home from scratch. San José del León was at that time a remote village lacking almost everything, no access to public services, poor roads, discontinued schooling and health attention, and very limited economic opportunities for campesinos (rural agricultural workers).

From the beginning, the reincorporated group of ex-combatants forged a close relationship with the neighboring communities, mainly campesinos. Despite the differences in their pasts, both ex-combatants and campesinos shared the same present—one marked by severe poverty and institutional abandonment. A shared identity based on the problems they were facing elicited close cooperation between ex-combatants and the San José del León community. This first manifested itself in the coordination of a joint campaign to restore the schooling services for children, one of the most pressing issues in the village. PASO Colombia and Ceiba (a local NGO), started to support the establishment of productive projects (via the ERA) and facilitate coordination efforts with local/regional governments and international organizations to improve the living conditions of the burgeoning community and others surrounding them.

The joint effort integrated the two groups, now seeing themselves not as separate, but instead as all members of the San José del Leon village. The now integrated population led to an increase in the responsiveness of local and regional authorities to support the improvement of living conditions. The Mutatá City Hall provided the materials to build a 4-kilometer road to connect the village with the main regional highway. Campesinos and ex-combatants provided the labor in this endeavor. Electricity service was also established for the first time in San José del León and surrounding villages. Rural schools and regular health campaigns were reactivated.

Other neighboring local governments, such as Riosucio City Hall, also helped the reincorporated group with materials to build 56 houses and a community center. The regional Antioquia Government purchased an 80-hectare farm to boost productive projects for the reincorporated population and campesinos, supported food security projects and nutrition campaigns, and facilitated the connection with other key public stakeholders such as the Antioquia University and regional private companies.

With PASO Colombia serving as a coordinating partner alongside other international organizations such as UNDP, World Food Programme, and the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, nine collective and eight individual fish farms in La Fortuna river were established. Here cachama and tilapia are farmed and sold locally. Animal feed is produced with local resources and crops serve as protein banks, resulting in a healthier, cheaper, and environmentally friendlier product. To ensure food self-sufficiency for the residents (a priority for ex-combatants), gardens, crops, and sheds for egg-producing hens were also installed. These initiatives have progressed with the help of campesino families from village hamlets, who also benefit from these projects.

The case of Mutatá illustrates how in ERAs that have a strong connection between reincorporated people and local communities and ongoing collaboration with local institutions, the level of trust is higher than the average trust levels across all ERAs.

Drawing from three years of survey data, we see that in 2020, 56% of Mutatá participants reported improved trust in local government while the average trust improvement level across all ERAs was 35%. Even though in 2019 trust levels decreased across the board mainly due to local government transitions via elections, the Mutatá participants' trust levels have remained higher than the average of all ERAs since 2018.

Telling a parallel story regarding trust, the survey inquired about trust levels between ex-combatants and local communities. In Mutatá, 86% of ex-combatants improved their trust in local communities while 70% of community members improved their trust in ex-combatants during 2020, both reaching the same or higher levels than the general average across all ERAs: 82% for ex-combatant-to-community trust and 70% for community-to-ex-combatants trust.

The collaborative networks built around the ERAs, and particularly the role played by local authorities to improve key basic infrastructure and services such as roads, housing, access to electricity, education/health, as well as the strengthening process of productive local capacities, have not only contributed to improving trust levels in local authorities but also the security perceptions of participants. Despite the adverse security and risk levels in rural Colombia after the signing of the peace accords (roughly 300 FARC ex-combatants have been killed since 2016), in Mutatá, 77% of respondents feel safer in the ERA than in other places, while the general average of this variable across all ERAs is 65%.

ERA Vignette: Fonseca

In Fonseca, an ERA was established within the original Territorial Training and Reincorporation Space (ETCR in Spanish) located in the Nueva Colombia farm in “El Conejo” village. In 2018 the ex-combatants cooperative (Coompazcol) started a laying hen husbandry project led by ex-combatant women, as part of its social and economic reincorporation process. The project was supported by PASO through the ERA activities and other international organizations such as the World Food Programme, the UN Verification Mision, and the International Labor Organization (ILO).

In its initial stages, the project was focused on the acquisition of the hens and the establishment of poultry houses. During the first year, the local authorities accompanied the process by attending meetings with the ex-combatants cooperative (Coompazcol) and providing technical assistance to specific productive initiatives within the reincorporation space (ETCR). The hens project, however, grew rapidly by selling the produced eggs. Notably, during the pandemic when food supply issues led to a spike in egg prices, the ex-combatant-led cooperative maintained the same prices and made eggs available not only to the reincorporated population but also to surrounding communities. Facilitated by the local PASO extensionista (the last mile PASO representative who serves as a point-person with the communities PASO works with), women from neighboring villages such as Pondores, La Unión, Las Colonias, Las Marimondas, and Las Bendiciones showed interest in joining the project by producing their own eggs and expanding its impact to even more communities.

The leaders of these villages, through their Community Action Councils, started to coordinate activities with Coompazcol, the aforementioned ex-combatants cooperative, and around 80 campesinos became members of the cooperative. Two community members were directly hired by it to support the hens project and a rural supplies shop administered by the cooperative. With the support of PASO Colombia, the project improved the productive infrastructure and its sustainability. PASO facilitated the provision of additional sheds and crops to supplement the animals' diet. Throughout the process, neighboring communities were also trained on productive and commercialization capabilities.

Between 2020 and 2021, the hen's project started to scale up the egg production with the goal of increasing the number of hens from 3,000 to 8,000, producing roughly 1,400,000 eggs per year. This scale-up endeavor was jointly presented to the Fonseca City Hall by the ex-combatants cooperative and neighboring communities as an economic development project that would benefit the whole “El Conejo” village. The organic connection between ex-combatants and neighboring communities, as well as the achievements reached through the egg production venture, triggered more robust support from local authorities for the project. In late 2021, local government institutions provided 5,000 hens to help their scale-up activities.

The networked coordination approach with communities as main partners has proven effective in improving productivity and reducing the costs of rural enterprises in a socially and environmentally sustainable way. This coordination support focuses on bolstering their work and collaboration capacity, improving their production practices, strengthening collective infrastructure, and creating value chains and new markets. It has also been a cornerstone element to increase the sensitivity and support from local authorities to the community. This has resulted in a transition from base-level support (for example, attending meetings and providing technical assistance) to an ever more direct and substantive support evidenced by funding to scale up the egg production project and facilitating the establishment of relationships with other government authorities and external stakeholders that provide different resources.

The survey results in the Fonseca ERA have shown significant levels of trust improvement in local authorities. In 2019 (when the survey started to be applied in this ERA), 17% of the participants reported an improvement in their trust in local authorities. This result was below the 29% average trust improvement in local authorities across all ERAs. In 2020, however, 50% of Fonseca participants reported an improvement in their trust in local authorities, almost tripling that in 2019 and significantly exceeding the 35% average across all ERAs.

Trust between ex-combatants and community members in Fonseca has also exceeded the national average

In 2020, 96% of ex-combatants in Fonseca improved their trust in local communities, compared to the national average of 82%. On the other hand, 100% of community members reported an improvement in their trust in ex-combatants in 2020, compared to an average of 70%.

These stories of success aren’t ones resulting from anyone given actor having all the answers or solving all the problems. Instead, they are the result of methodically and carefully unlocking the basic resources and support needed for ERA participants to increasingly assume agency over the improvement of their lives.

While PASO’s work and results make us proud, we believe they are an encouraging piece of evidence that non-governmental organizations can serve as a facilitator for distinct actors who many times struggle to work together. When each brings a needed piece of the proverbial puzzle, real problems can be solved. Institutions that partake in these efforts take the credit in the eyes of those who benefit from the collaboration. This work shows that even when things are bad—and maybe especially when they are—there are opportunities for building trust in local institutions.

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights