Eighteen Somali fisheries officers and data enumerators are leading a pioneering fisheries data collection project - the first since the country’s civil war.

by Laura Burroughs and Jamal Hassan

The project, known as the Fisheries Data Collection Working Group (FDCWG), is a nation-wide fisheries catch data collection program that seeks to produce national estimates of fisheries catch and economic contribution. It spans six landing sites and is supported by SF and FAO.

Those working at the landing sites are incredibly knowledgeable about their coastal ecosystems and quickly picked up a knack for data collection. After only eight months, data collectors identified and counted over 31,000 fishes and collected length and weight data on 8,400 fishes. They accomplished this by surveyinging three boats per day, three times per week, at each fish landing site. This ongoing project is a substantial effort, but they see the bigger picture: the contribution of their efforts to generate the information necessary to protect their coastal resources. Through the process of measuring and weighing fish, they are providing the first steps toward effective fisheries management informed by national-level data collection.

To better understand the impact of this project, Secure Fisheries interviewed two contributors to learn about their experiences. In 2019, Gani Hassan and Mohamed Gacal were hired for the FDCWG. Gacal is the project assistant; he is in charge of data entry and quality assurance, and he contributes to data analysis. Gani is a landing site data collection coordinator; she oversees the data collection work of her two data enumerators, submits completed data forms to Secure Fisheries, and collects data alongside the enumerators in the field.

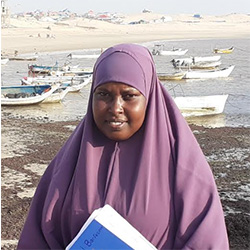

Landing site data collector Gani, left, and project assistant Gacal, right

Gani was born in Kismayo and holds a medical degree from Kismayo University, and a certificate in Business Administration. She worked for UNICEF in a pediatric ward and taught high school math and Somali language courses. In 2017, Gani became involved in the Somali fisheries sector through a project with GIZ and the Jubaland Ministry of Fisheries in Kismayo where she volunteered to collect data. Gani’s experiences collecting data have led her to become very interested and invested in the Somali fisheries sector.

Somali born, Gacal grew up in the United Arab Emirates. He returned to Mogadishu and achieved a degree in marine science from City University of Mogadishu. The program solidified his passion for Somali fisheries and he hopes to continue his studies through a postgraduate degree.

Both have learned important skills through the data collection activities. There are some very technical aspects to these roles, including fish identification and accurate fish measuring that have enabled Gani and Gacal to build their knowledge of Somali fish and hone important fisheries research skills. The skills they have developed are often put to the test when the data collectors encounter challenges in their work. For example, identifying fish is a difficult task that requires careful observation to distinguish between different species. Team members must also have a high level of patience and commitment. The data collectors sometimes wait on the beach for six hours before the first fishing vessel arrives.

This project has also highlighted broader challenges to the Somali fisheries sector, such as trust between resource users and government. At Lido Beach, a fisher accused Gacal of collecting catch data for the Turkish Embassy. This was an extreme case of mistrust, but it highlights some of the initial suspicion around data collection. There is a need to develop trust among resource users, scientists, and government officials. Gani also emphasized that trust is a vital component for a successful and long-lasting data collection system. Community members must understand and be involved in the project in order for it to be effective. These interpersonal skills and relationship-building efforts have paid off, ultimately leading to positive support for data collection from community members.

By spending time at the landing sites, the data collectors have seen the challenges faced by the fishers themselves. Gani’s position has given her firsthand experience of the extreme danger Somali artisanal fishers face. Gani’s team encountered the survivor of a fishing vessel that capsized, resulting in two deaths. Many fishers do not know how to swim and most do not have proper safety equipment. From Gani’s observation, these things “can make the difference between life and death.”

Regardless of the challenges, Gani and Gacal remain committed to and optimistic about Somali fisheries. Both emphasized the importance of reliable fisheries data for informed fisheries management, which the government currently lacks. They believe the Somali fisheries sector is improving. There is a lot of room to develop the domestic market. Somalis have not traditionally been fish consumers, but the market, and its corresponding job opportunities, are expanding. Gani is now seeing Somalis travelling from Merca to Kismayo to take advantage of opportunities in the fisheries sector.

Since the inception of FDCWG, Secure Fisheries’ project manager, Jamal Hassan, has observed that those working on the data collection project have begun to take on a sense of ownership of their work and their country’s natural resources. They see the national importance of the project and want to look after it. At the final workshop, Gacal told Hassan, “After having been entrusted with managing a national fisheries catch database, I feel the weight of the responsibility on my shoulders.” Through measuring fish, and collecting, managing, and reporting data, these Somalis are generating the information that will ultimately lead to better fisheries management in the Somali region, and therefore a healthy future for its vast ocean territory.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights