This is the third post in a five-part, weekly series on elections in dictatorships. Visit our CoupCast site for information about our REIGN database and previous commentary on coups d’état.

In Chile, Augusto Pinochet came to power in 1973 through a coup d’etat. Immediately after taking power, thousands associated with the political opposition were killed, forced into exile, or disappeared. A military junta was established after the coup that suspended the constitution and the legislative branch and imposed strict censorship and curfew laws. His rule was largely uninterrupted for fifteen years.

Pinochet was a typical dictator—until 1988. He unexpectedly lost a plebiscite that would have extended his rule over Chile for an additional eight-year term. Pinochet accepted the results and handed over power to a civilian government in 1990.

Almost 40 percent of dictators suffer an election loss.

Dictators in Chile, Taiwan, South Korea, and the Philippines lost elections and stepped down. When and why do dictators make the decision to allow elections and accept the results of those races? The REIGN dataset developed by OEF Research allows us to investigate these questions. For instance, peer-reviewed research produced with the help of OEF Research has demonstrated that dictators (who normally rise to power through unconventional avenues) are much less likely to exit through conventional methods such as elections.

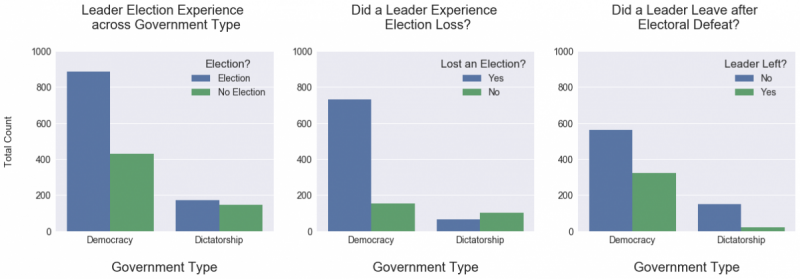

Using the REIGN dataset, we identify the proportion of leaders who leave office following elections in dictatorships as compared to democracies in all countries from January 1950 to the present.

Figure 1

Figure and Data Analysis by Clayton Besaw

Only 12 percent of dictators leave office after losing an election.

Though our focus is specifically on dictatorships, we use democratic elections as a comparison. The first panel calculates the portion of leaders who face elections in democracies as compared to dictatorships. Similar to democracies, the majority of dictators will hold an election while in office (as was discussed in the two previous posts in this series here and here). Interestingly, the second panel shows us that almost 40 percent of dictators will suffer an electoral loss while they govern the country. With that in mind, the third panel shows us that only 12 percent of dictators will make the decision to leave office after facing such a loss, with 88 percent ignoring the results and maintaining their control of the government.

Who stays in office and who leaves? The type of election matters.

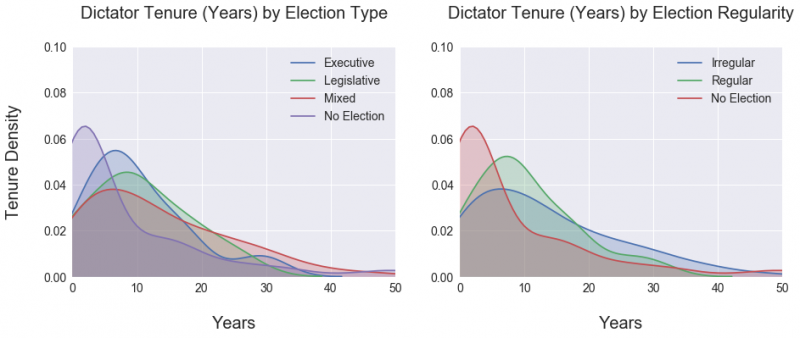

Figure 2 provides more guidance as to which dictators stay in office and which leave. It appears that the type of election matters. The two panels chart the kernel density of leadership tenures for dictatorships. For instance, dictators who host irregular elections tend to have longer tenures as compared to dictators who host regular elections. Tenures also tend to be longer when dictators host legislative or mixed elections. This is especially true after the first twenty years in power.

Dictators who have shorter tenures tend to not experience elections or only experience executive elections. Specifically, the density peak for dictators who host only executive elections is much shorter than density peaks for legislative elections. This finding is supported by academic research. As noted by Jennifer Gandhi and Adam Przeworski, dictators often host partisan legislative elections to identify potential challengers in society and incorporate them into the government.

Figure 2

Figure and Data Analysis by Clayton Besaw

Military dictators are the most likely to step down from power.

Twelve percent of dictators who lose elections accept the loss and leave office. As noted by Curtis Bell in a previous post for this series, dictators may be caught off guard by a sudden loss. It should be noted that this is often the case for military dictatorships. While the data above do not answer this question, previous academic research suggests that of all dictator regime types, leaders of military regimes are the most likely to step down from power.

When military dictatorships hold multiparty elections and maintain a legislature, they are much more likely, as compared to other dictatorships, to transition to democracy. Equally, the presence of legislatures that host (at least nominal) opposition parties significantly reduces the likelihood that former dictators will be killed or jailed once they step down from power.

This is largely because military dictators are able to return to the barracks. Military dictators may assume a leadership role of the armed forces once they abdicate power. This was the case for Pinochet. Once out of office, he maintained control of the armed forces for eight more years. Equally, he was granted immunity given his status as a former president of Chile. Though he was finally stripped of his immunity in 2000, the old dictator avoided conviction for crimes against humanity until his death in 2006.

It is rare for dictators to step down, but when they do it is because, like Pinochet, they have a feasible alternative, such as rejoining the military, that allows them to avoid accountability for human rights abuses.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights