The violence the world witnessed at the US Capitol on January 6 is no exception to what we have observed internationally for more than a decade in terms of drivers of political violence and conflict. In this issue, OEF Senior Strategic Advisor Conor Seyle dives into what we can learn about moving forward.

The violence the world witnessed at the US Capitol on January 6 is no exception to what One Earth Future has observed internationally for more than a decade. While it may have come as a surprise to many, analysts monitoring the situation in the US have been sounding an alarm for months that similar violence was possible. Even likely.

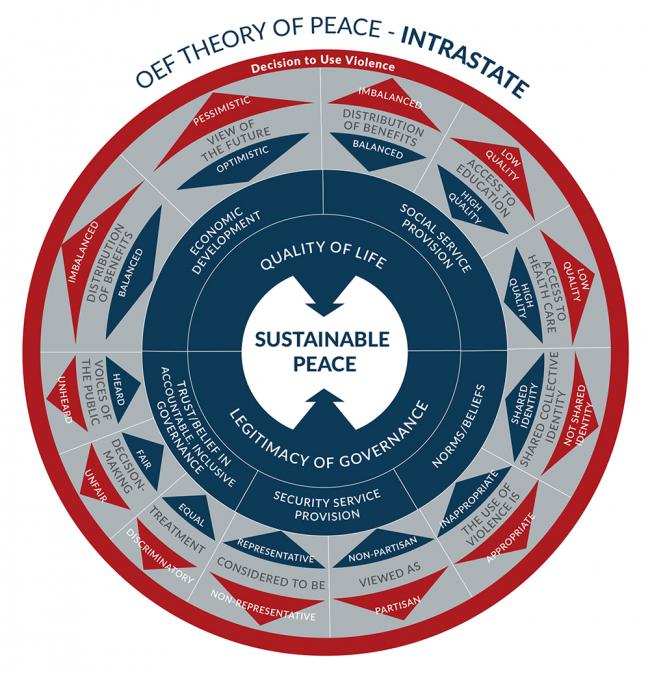

In order to do our work, OEF has developed a theory of peace and war that helps us understand the drivers of violence internationally. Civil war and organized violence within countries is the most common and most lethal form of violence, and the drivers of this kind of conflict are well-understood. The graphic below shows how OEF thinks about organized political violence and what drives it within any country. This kind of violence is always the result of multiple pressures colliding with crisis moments and elites who support the use of violence for political means.

At the structural level, violence is significantly more likely when people have less to lose. When people feel optimistic about the future and have access to economic resources and social services such as health care and education, they are less likely to use violence. Similarly, violence is less likely when people trust that their political institutions are fair and legitimate: when they trust using a court system rather than violence to resolve a dispute, most people will. This is one reason why maintaining a population’s widespread belief in the legitimacy of institutions is such a critical part of peace. Norms are also crucially important: once people accept that violence is an appropriate tool, either for political goals or against some group or “other,” a line will have been crossed that is hard to recover from.

These structural pressures are the tinder for conflict, but still require a spark. Crisis moments - often around elections and other events that bring on a rapid change in people’s sense of threat or their idea of what’s possible or appropriate - can create conflict spirals where violence breeds more violence. The role of elites, thought leaders and movement leaders who can influence people’s understanding of what happened or turn out large groups of people at specific moments, is extremely important. Their words and actions are pivotal in whether these crisis moments escalate into larger conflicts.

Within this framework, a sober assessment of the United States makes it difficult to escape the conclusion that the violence at the US Capitol was neither unusual or something that won’t recur. Considering the underlying issues of economic opportunity, social services, and overall quality of life for a large number of US citizens, the US has been falling behind on these issues for decades. Income inequality is increasing while economic mobility is decreasing and, in particular racial gaps in wealth and education are widening. Access to healthcare and quality education lag behind other developed countries significantly, and life expectancy is flattening for Americans. Such structural pressures create discontent that can be captured by political movements and used to mobilize turnout or turn one group against other groups in society.

Considering our institutions, political polarization has spiked over the last few decades in ways significantly beyond the polarization in other Western democracies. This has corresponded with increasing distrust in our political institutions and an increasing weakness of our democratic institutions - distilled recently into the poisonous claim that the Presidential elections were fraudulent. The Fragile States Index ranked the US as one of the five “most worsened countries” for political stability in 2018. At the same time, acts of political violence are increasing and social media calls for “revolutions,” “guillotines,” and “trials for treason” are undermining the idea that violence is not an appropriate tool in the realm of politics.

With this tinder in place, sparks become important. The signals sent by elites in the long lead-up to the violence at the US Capitol on January 6th, and indeed while it was going on, were more than sufficient to spur violence. Language of “wild protest,” “stolen elections,” and calls to “defend the American way of life” coincided with specific plans for mobilization calling for people to turn out at a specific point in time. The violence wasn’t random or unexpected: it was the clear result of an obvious set of pressures coinciding with a specific mobilization, and the only thing that made it unusual to watchers of political violence was that it happened in the United States.

Had the same event taken place in a country with a history of violence, it would have been seen not as an unusual event, but instead as the predictable outcome of the conditions and rhetoric in that country. When commentators said that this could not have been seen coming, or when Secretary of the Army Ryan McCarthy admitted that the government didn’t think such a breach was possible, they reflect a widespread perception that “it can’t happen here” that is based on little more than a faith in US exceptionalism and the precedent of our history. The United States is not exceptional in this way, it has become clear. When the conditions in the US are viewed through OEF’s theory of peace it can not be surprising how likely this violence was, and continues to be.

The structural pressures that created the afternoon of violence at the US Capitol have not gone away. Instead, with the weakening norms against the use of violence combined with the now challenged credibility of the political institutions following their inability to control the riot, they have, if anything, become worse. If these structural pressures are allowed to continue - if polarization continues and no change is made to the material conditions of people in America, and if violent rhetoric is not condemned and excluded - then the only question will be what kind of elite signals and what kind of sparks come through in the future. The violence at the Capitol wasn’t unexpected. It wasn’t unusual, in the context of violence internationally. The lessons of violence globally also tell us, on the whole, that if nothing changes in terms of the pressures and politics of the US then the violence at the Capitol won’t be the last organized political violence in the United States in the coming weeks or years either.

Our hope is that the lessons of this week and recent years will be taken to heart in ways that could offer a positive turning point for 2021. The fact that the United States isn’t exceptional is good as well as bad: other countries have demonstrated the slow growth from political violence to stability and there’s nothing that would prevent the US from taking the same course. If we choose to.

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights