World peace has a bad rap but the truth is, peace has been doing pretty well in the 85 years since World War II.

World peace has a bad rap. Pacifists are dismissed as dreamers. “Peacenik” became a derogatory term. And with all due respect to John Lennon, he may have done a disservice to non-violence by relegating it to the realm of the imagination.

World peace has a bad rap. Pacifists are dismissed as dreamers. “Peacenik” became a derogatory term. And with all due respect to John Lennon, he may have done a disservice to non-violence by relegating it to the realm of the imagination.

The truth is, peace has been doing pretty well in the 85 years since World War II wrought its terrible toll. As experienced international journalists, we have reported on the many ways that humans have made unfathomable progress improving living standards, reducing armed conflict, and creating wealth. You wouldn’t know it by reading the headlines, listening to political candidates, or following Twitter feeds, but the world is experiencing fewer wars, less sexual violence, higher educational attainment, lower infant mortality rates, and lower homicide rates than any time in history. There are plenty of exceptions, but the global reality is this: Pretty much everywhere in the world, there’s been an outbreak of non-violence.

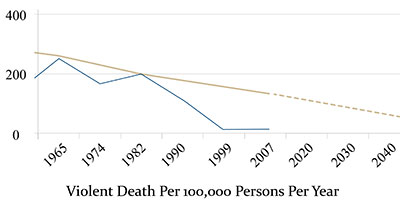

At a recent forum hosted by One Earth Future Foundation (OEF), an organization that works toward preventing and stopping armed conflict, we heard ambassadors, activists and academics address a deceptively simple question: What will it take to achieve enduring peace in the 21st century? This thoughtful group considered the range of data indicating that the actual state of violence in the world contrasts with the headlines. Since the end of World War II, the decline of combat has been dramatic. In 1950, the annual rate of reported battle-related deaths was approximately 240 per million of the world’s population; in 2007, it was less than 10 per million. There are no wars between two countries’ armies currently occurring anywhere in the world. Homicide rates in almost every country have dropped. Violence against women and against children is on a steady decline. In sub-Saharan Africa, where the U.S. media’s primary interest is in war, disease, and famine, two thirds of the population (650 million people) lives in stable enough democracies to enable GDP growth rates of 5.3% in 2014.

At a recent forum hosted by One Earth Future Foundation (OEF), an organization that works toward preventing and stopping armed conflict, we heard ambassadors, activists and academics address a deceptively simple question: What will it take to achieve enduring peace in the 21st century? This thoughtful group considered the range of data indicating that the actual state of violence in the world contrasts with the headlines. Since the end of World War II, the decline of combat has been dramatic. In 1950, the annual rate of reported battle-related deaths was approximately 240 per million of the world’s population; in 2007, it was less than 10 per million. There are no wars between two countries’ armies currently occurring anywhere in the world. Homicide rates in almost every country have dropped. Violence against women and against children is on a steady decline. In sub-Saharan Africa, where the U.S. media’s primary interest is in war, disease, and famine, two thirds of the population (650 million people) lives in stable enough democracies to enable GDP growth rates of 5.3% in 2014.

Given these positive trends, OEF forum participants who gathered to consider the possibility of global peace in the 21st century were perplexed. Why, they wondered, does the dominant narrative lead us to believe we are living in darkening, dangerous times? This storyline is both untrue and self-defeating, and the concept of promoting peace isn’t any more naïve than the concept of promoting health. Achieving both are complex challenges, but just as we developed vaccines to improve global health in the 20th century, we now have the tools to inoculate ourselves against war in the 21st century.

Unfortunately, we haven’t made much of a global effort to plan, assess trends, and learn from the things that haven’t turned out so well. We believe we have reached a point in humanity’s course where a failure to plan for peace will ultimately result in catastrophic failures that are predictable and preventable. It is foreseeable that an increase in war and conflict will lead to an epidemic of suffering. It is also expected that careful interventions that reduce conflict can build support systems by seeding more of what works, while weeding out what doesn’t.

War, almost everywhere, represents a profound failure of planning and a guarantee of future conflict. We have seen the devastation that occurs when we don’t plan. Roméo Dallaire, the general who oversaw the Rwandan genocide, argues convincingly that 5,000 UN troops sent early on would have avoided the death of 800,000 people. Even the current Ebola epidemic was predictable and containable, if we were only prepared as a global community to act decisively. We see the specter of climate change materializing before our eyes with enormous potential to create more conflict, yet world leaders rarely cooperate on effective, preventative actions.

We wonder why early warnings continue to go unheeded, why seemingly isolated events such as crop failures, small-scale police actions or viral messages on social media aren’t seen as early indicators of impending conflict. Why are credible alerts from citizens and community-based experts routinely ignored? It doesn’t require much imagination to make sense of what might appear to be unrelated events and information. It requires a willingness to merge large conceptual models such as systems thinking with on-the-ground, “bottom-up” approaches to identifying patterns that lead to conflict, or conversely, replicating those patterns that promote peace.

We wonder why early warnings continue to go unheeded, why seemingly isolated events such as crop failures, small-scale police actions or viral messages on social media aren’t seen as early indicators of impending conflict. Why are credible alerts from citizens and community-based experts routinely ignored? It doesn’t require much imagination to make sense of what might appear to be unrelated events and information. It requires a willingness to merge large conceptual models such as systems thinking with on-the-ground, “bottom-up” approaches to identifying patterns that lead to conflict, or conversely, replicating those patterns that promote peace.

One answer that emerged from OEF’s forum is that we need to learn more about what works and why, and avoid actions that are doomed to fail. We know empirically that economic development works better than dropping bombs, and involving more women in decision-making achieves better results than sending soldiers with automatic weapons. Why not put that data and empirical evidence to work for us – and focus more research on diagnosing, preventing and curing conflict?

Those who convened for this forum weren’t mushy-headed about the prospects for world peace. Humanity faces some serious problems. Billions of people suffer from a lack of basic necessities, like clean drinking water, a living wage, and a way to educate their children. Current conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, and Syria – and the unnerving barbarity of ISIS – can’t be ignored. Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed in Algeria, Bosnia and Rwanda, where the horrors of world war have been replaced with intra-state conflicts. But in almost every case, these are not fundamentally religious wars or ethnic wars; they emerge from poverty and hopelessness and spread through unresolved conflict, weak institutions, and power grabs by madmen.

Humanity needs a plan for peace. Our world has grown too complex, with too many people, with challenges too profound, and stakes too high to keep blundering on without blueprints. We need to construct plans that build on what we’ve been doing right and recognizes that humans are hard-wired to make sacrifices for their children – and have been in every human society across time.

Humanity needs a plan for peace. Our world has grown too complex, with too many people, with challenges too profound, and stakes too high to keep blundering on without blueprints. We need to construct plans that build on what we’ve been doing right and recognizes that humans are hard-wired to make sacrifices for their children – and have been in every human society across time.

This is not a tilting-at-windmills proposition. Drastic changes in thinking have happened over time. Things that humanity used to accept as normal, like throwing virgins into volcanoes and owning slaves, have become anathema. We can measure our progress or lack of progress towards peace using metrics that people around the world can agree on: the health of our children, the frequency of armed conflict, the relationship of domestic spending to military spending.

For this to happen, world peace needs a makeover, a re-branding, a global marketing effort, a viral campaign. It really isn’t a hard sell for most of our seven billion people; after all, who is advocating for escalating bloodshed? Sure, there are dysfunctional belief systems out there, as there have always been. But these are minority beliefs, and it’s not a pipe dream to think that we can eradicate war in our century, all the more as our economies, environment and our families are joined in ever more symbiotic ways. People from all over the world, from different religions, cultures, and languages are intermarrying; businesses are forging supply chains that span continents; cultural icons that connect generations are not bound to their countries of origin.

We’ve actually been giving peace a chance, and this contagion could spread. Not by dreaming, but by concentrating on humanity’s incredible resourcefulness on what would benefit seven billion people and counting.

We’ve actually been giving peace a chance, and this contagion could spread. Not by dreaming, but by concentrating on humanity’s incredible resourcefulness on what would benefit seven billion people and counting.

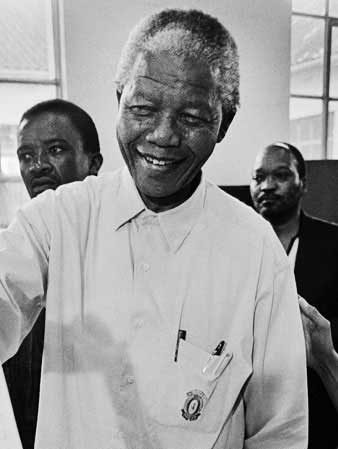

We have no illusions that there will be world peace in our lifetime. But organizations like OEF are committed to making the 21st century a century of peace – not through hundreds of romantic notions but by solving hundreds of solvable problems. There is will. There is a way. As one of the forum’s attendees said so aptly, “I’m too old to take on anything difficult. I’m only interested in the impossible.” Because, as Nelson Mandela told us, something is only impossible until somebody does it.

Leslie Dodson and Daniel Glick

Lafayette, Colorado

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights