Empirical research shows that the presence of peacekeeping missions at or near full deployment significantly reduces violence against civilians. However, UN peacekeeping missions are often slow to deploy.

Peacekeeping operations have come under fire in recent years. Many have criticized the failure of missions to end ongoing conflicts. They have also pointed to the exploitation and abuse of civilians at the hands of peacekeepers themselves. These observations come at a time when peacekeeping operations are under additional pressure due to cuts in funding and the potential for more.

However, scholarship on peacekeeping shows it offers a net positive effect. It is one of the few tools the international community has to counter active conflict around the world. So what are some of ways policymakers might improve it?

In the next few weeks, our OEFR team will offer suggestions on how peacekeeping operations can be made more effective in the years to come.

Faster Force Deployment

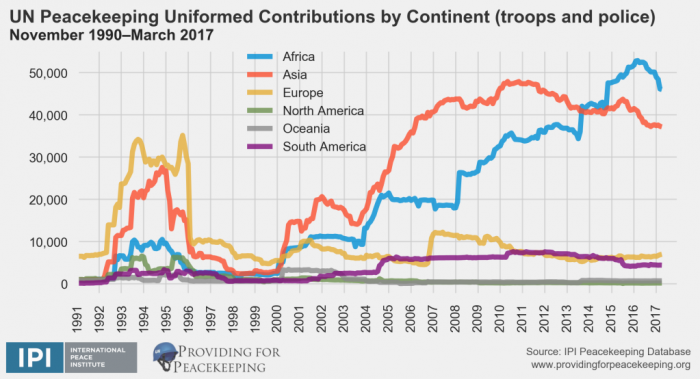

UN peacekeeping missions are often slow to deploy. Over the last 25 years, UN peacekeeping missions have taken an average of ten months to reach peak deployment. That is ten months in which the UN may have declared a conflict a crisis of global priority, but has still failed to effectively intervene.

Such delays have devastating effects on civilians. Conflicts can intensify and spread, sides may become further entrenched, and political solutions can become more difficult to achieve. The longer it takes a force to fully deploy, the more the situation is likely to devolve. Empirical research shows that the presence of peacekeeping missions at or near full deployment significantly reduces violence against civilians. As the nature of UN peacekeeping evolves toward more frequent peace enforcement interventions, such as that of the Force Intervention Brigade in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the speed of deployment becomes even more critical. There is evidence to suggest that peace enforcement of this kind initiates an increase in the use of violence against the civilians by the armed group faced with intervention. Slowly deploying peace enforcement missions can increase threats toward civilians before troops arrive to protect them.

So what can be done to increase the speed of deployment?

In the short term, the UN should partner with other organizations to get boots on the ground quickly. Providing non-UN actors with the mandate to undertake rapid intervention and stabilization will help. These short-term operations can then be handed off to UN personnel as soon as they are able to deploy. We have seen successful examples of this with individual nations, such as the French intervention in Mali. Regional organizations can also serve this purpose. Examples of this include the African Union’s role in Darfur and The Economic Community of West African States intervention in Sierra Leone. Further institutionalization of these arrangements should be pursued as a stop gap measure.

While advanced militaries are hesitant to contribute troops to UN missions they may be willing to provide services that help others deploy more quickly, such as transporting the troops of other countries to the mission area. They can also supply the kind of supporting services necessary to successfully execute the mission. Advanced militaries, while often reluctant to deploy infantry, have significant expertise in these operational capabilities and may be willing to provide the transportation, field hospitals, engineering units and logistical expertise that would allow forces to deploy more quickly.

Check back in next week when we discuss improving the intelligence gathering and analysis capabilities of peacekeeping operations.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights