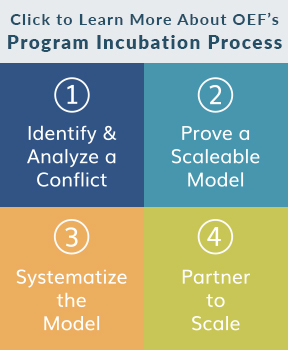

Our core organizational strategy and values require us to take seriously the idea that our goal is to catalyze systems that are sustainable, that are scalable and—most importantly—that actually address problems underlying conflict. So we’ve developed a theory of incubation, based on iteration and scaling, which helps us navigate this challenge.

One Earth Future believes that because the causes of political violence are so complex, creating sustainable peace requires coordinated work across multiple issue areas simultaneously. We have some ideas about how to do this, but that by itself some may perceive as grand theory. In our work on the ground across Somalia, Colombia, and elsewhere, we have had to develop approaches that translate that theory into specific and impactful work. The core problem we confront in doing so is this: how can we, as a small to medium-sized NGO within the larger field of peace and conflict (not to mention governments), work effectively in a complexity-informed way that actually operates at the scale of the problem we’re trying to address.

As an NGO, we have relatively limited ability to operate compared to the other actors in the space. We have a fraction of the financial resources and organizational breadth of the weakest government in the areas where we work, not to mention those governments that fund large-scale, centrally planned initiatives from afar. While we may be able to set up programs that address specific challenges or issues in areas where we operate, the nature of who we are means that we will rarely, if ever, have the capacity to single-handedly support work that is at the scale of the large societal dynamics that drive conflict.

OEF was founded with a long-term, whole-of-humanity perspective in mind, articulated in our audacious mission, the elimination of armed conflict within this century. As an organization, we find ourselves having to carefully balance this mission with the very real challenges and limitations of moving the needle in that direction from current reality. While we soberly recognize the limitations, our core organizational strategy and values require us to take seriously the idea that our goal is to catalyze systems that are sustainable, scalable, and—most importantly—that actually address problems underlying conflict. So we’ve developed a theory of incubation, based on iteration and scaling, which helps us navigate this challenge.

When we decide to invest in a program, our intent is to design something that is demonstrably contributing to peace, can work at a scale that matches the problem, and integrates into a complex system. To do this, we design for scale but start small and sequentially grow that which proves it can work. We start by scoping our work with a conflict analysis (based on the excellent existing guidance on mapping conflicts), which helps us develop our theory of the conflict—the driving forces and how they interact. Based on that model, we then identify a single node—a narrow, specific point of entry that is at the intersection of being underserved and matching our core organizational competency of networked coordination. We then perform initial research on the issue to develop a working “RNDP,” or Rigorous and Narrow Definition of the Problem, and “UVP” or Unique Value Proposition that lays out our theory of what and how we can operate. This is part of a reciprocal process of idea development and validation: we pitch this idea to key stakeholders, solicit their feedback and adapt the idea based on it, until we’ve reached a point of saturation and have gained enough momentum to formally hire a Director to finalize plans based on their expertise and experience. We did this most recently with Open Nuclear Network, first developing a rough-draft theory of impact and validating it with dozens of experts and stakeholders over a period of months, but not finalizing our scope and plans until Laura Rockwood, an expert in nuclear regulatory issues and nuclear diplomacy, came on to guide program plans forward.

When we decide to invest in a program, our intent is to design something that is demonstrably contributing to peace, can work at a scale that matches the problem, and integrates into a complex system. To do this, we design for scale but start small and sequentially grow that which proves it can work. We start by scoping our work with a conflict analysis (based on the excellent existing guidance on mapping conflicts), which helps us develop our theory of the conflict—the driving forces and how they interact. Based on that model, we then identify a single node—a narrow, specific point of entry that is at the intersection of being underserved and matching our core organizational competency of networked coordination. We then perform initial research on the issue to develop a working “RNDP,” or Rigorous and Narrow Definition of the Problem, and “UVP” or Unique Value Proposition that lays out our theory of what and how we can operate. This is part of a reciprocal process of idea development and validation: we pitch this idea to key stakeholders, solicit their feedback and adapt the idea based on it, until we’ve reached a point of saturation and have gained enough momentum to formally hire a Director to finalize plans based on their expertise and experience. We did this most recently with Open Nuclear Network, first developing a rough-draft theory of impact and validating it with dozens of experts and stakeholders over a period of months, but not finalizing our scope and plans until Laura Rockwood, an expert in nuclear regulatory issues and nuclear diplomacy, came on to guide program plans forward.

We know this program won’t create peace by itself, even within its issue area or conflict context, and we expect it to be wrong in some key ways as yet unknown in the early stages of implementation, so we go through a process of iterative testing. It’s there where we start to develop operations under this theory of impact, but frequently pause to reflect on measured progress and identify whether it’s achieving its intended impacts or not.

One Earth Future intentionally invests in the time and resources necessary for the program to establish itself within the conflict area in the first year, establishing access, building credibility and earning trust with relevant actors by demonstrating competence, listening to stakeholders, and adding value. We know it will take time for the working theory of impact to take shape as it goes from being “on the desk” to “on the ground,” so we are very hands on in the formulation of the program’s model—the cohesive set of projects that together achieve desired outcomes.

Through all of this, as a matter of course we articulate comprehensive and specific yearly goals that are in accordance with progressive stages and increasing expectations of impact. Through our monitoring and evaluation framework, we gather data surrounding the implementation of each program’s model, their progress in demonstrating impact effectiveness, and stakeholder perceptions. We use this data to measure progress and impact against our impact hypothesis as well as bigger picture trends in the social and conflict context. Throughout, we place emphasis on not getting stuck on our original thoughts and expectations of what success would look like during the planning process—we seek to proactively acknowledge and make sense of unexpected successes, context changes, and new opportunities in order to develop a nuanced understanding of what is working and what is not.

Based on this learning, we iterate the program and its model—even going as far as changing fairly fundamental aspects if needed. Our Shuraako program in Somalia, for example, launched with a mandate to catalyze international funding for Somali businesses (a tall order in the summer of 2012). Based on findings from our initial reviews of our efforts, the program shifted in its first year from a starting plan to match external investors to investment-ready Somali businesses to a program that acted to directly make investments—first from our own endowment, then as an agent of larger development organizations.

Once a program has a model for impact backed up by evidence and a track record of replicability, we move to scale. We work to systematize the implementation of the program’s work, making it more cost effective, eliminating that which is superfluous, creating internal processes and systems, restructuring the organization and roles, and implementing practical tools such as information management systems. We seek out implementation and funding partners that have alignment with the program’s model and value add. These partners are the key to our ability to replicate or extend the reach of the program model until it works at “a scale that matches the problem”—a scale where our networks are collectively impacting large conflict systems through models that have been proven to work.

While we are doing this, at this stage we also look for ways to expand our impact outside of the narrow and specific point of entry, to move into further addressing the system as a whole. Some of this happens organically, as we identify issues related to our work that we can and need to address, or identify issues that will affect the success of our programs. It also occurs based on discovery of areas of overlap with funding partners, which enables us to continue to implement our core model at a larger scale, but also broadens the range of opportunities to contribute to different stakeholders and other problems underlying conflict. For example, our PASO Colombia program evolved from a narrow initial focus on supporting economic and social reintegration of former combatants and their community to utilizing the model that emerged as a result, the Rural Alternative Schools (ERAs). ERAs were pioneered by OEF, weaving partnerships with and between community-led cooperatives, local government, companies like Hugo Restrepo & Co. and Illy Coffee, international organizations like the UN and Aid Live and local governments to address broader and directly related rural issues of development and stability through crop substitution and migrant integration.

We don’t only grow in that organic fashion. Some of our networked impact happens directly and strategically through attempts to directly catalyze networks for impact across broad issue areas. One example of this can be seen in the Our Secure Future program’s participation in the establishment of the first Women, Peace, and Security Caucus at the US Congress.

We call this process an “incubation” for several reasons. First, we believe that emergent, innovative solutions to complex problems require, somewhat paradoxically, a patiently urgent process that balances structure and adaptability.

Next, because growing a small-scale operation to meet problem scale requires holding the long-term vision in mind from the beginning and being able to think systematically and pragmatically where needed. Further, our goal is not to have these programs go out and be another program doing good work independently, and as a result falling victim to the “grant carousel” that tends to stifle context- and complexity-informed approaches.

Instead, we aim to invest the time and resources to develop an approach that is backed by evidence, which will eventually be spun off to operate at scale and in a self-sustaining way. Or, alternatively, that we will work our programs out of business by the creation of a sustainable network of actors working in concert with each other.

In developing this approach, we’ve tried to balance the need to implement at scale and for the long term, with the need to build space for continual learning to nimbly and accurately iterate our work. In our decade of experience, this approach demonstrates that even small organizations can take seriously the need to work at the scale of the problems facing conflict-affected states, and develop tools for how to do so. Whether our approach actually helps deliver peace, or not, is of course, a question that this process is designed to help answer, but we hope that at minimum this provides a way for other organizations to think about how they, too, can address questions of complexity and scale.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights