This is the fourth post in a five-part, weekly series on elections in dictatorships. Visit our CoupCast site for information about our REIGN database and previous commentary on coups d’état.

Since independence in 1960, Burkina Faso has experienced ten coups or attempted coups. Six of these occurred in the 1980s. A long period of stability followed during the reign of Blaise Campaore, which was interrupted by violent protests and a change in leadership in 2014. A coup attempt collapsed in 2015, and the government thwarted a 2016 coup attempt.

Blaise Campaore came to power via coup in 1987. He won four noncompetitive elections before he was overthrown in 2014. Supported by the armed forces, the transition of power was overseen by Lt Colonel Isaac Zida and he was replaced by Interim President Michel Kafando. In 2015, a coup by the presidential guard removed Kafando from office a month before elections were scheduled to take place. This coup collapsed a week later, and Kafando was reinstalled. The 2015 general election resulted in the presidency of Roch Marc Christian Kabore, the first non-interim president in Burkina Faso’s history without any ties to the military.

However, Burkina Faso’s legacy of coups continues. It still ranks consistently as one of the countries at greatest risk for a coup in CoupCast—a predictive model that OEF Research developed to predict the likelihood of a coup in any country on a monthly basis.

Based on the experience of Burkina Faso, it is easy to assume that successive coups are quite common. Is it true that coup begets coup? The REIGN dataset can help answer this question. The REIGN dataset collects data on elections in every country, every month starting from January 1950 to today.

There are more coup attempts in countries that hold elections.

Figure and Data Analysis by Clayton Besaw

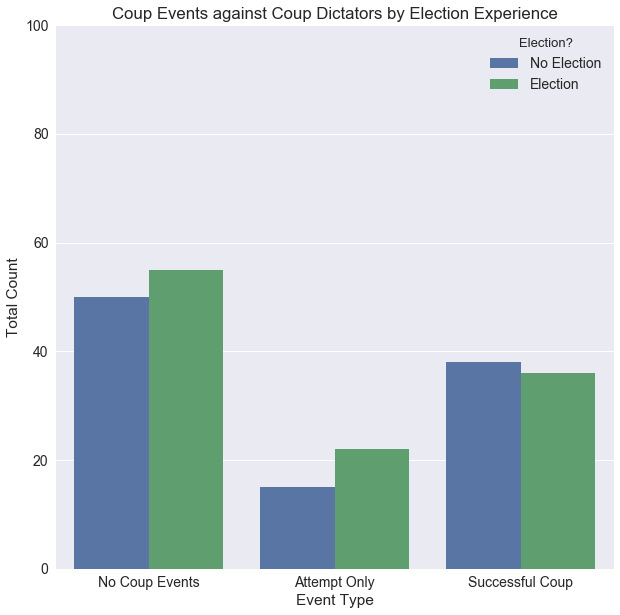

A previous post in this series showed that the risk for coup is highest in the lead-up to an election but falls sharply after an electoral victory. Relatedly, the figure above shows the number of dictators who come to power via coup. It also shows the number of dictators who experience a coup attempt, who do not experience a coup attempt, or who experience a successful coup, which throws them out of power. This is then differentiated based on whether they hold elections.

There are more successful coups in countries that do not hold elections, and more failed coup attempts take place in countries that do hold elections. In our sample of dictators who held elections, 55 had no coup attempts (or 25 percent), 22 had a coup attempt (or 10 percent), and 36 had a successful coup (or 17 percent). When dictators did not hold elections, 50 had no coup attempt (or 23 percent), 15 had a coup attempt (or 7 percent), and 38 had a successful coup (or 18 percent).

Surviving a coup attempt and/or winning decisively in an election can help to entrench a dictator’s power— as discussed in previous posts in this series (here and here). It may also mitigate the chances of future coup attempts. In fact, as the REIGN data show, successive coup attempts are incredibly rare.

Most dictators who come to power via a coup experience at least one coup attempt, but multiple coup attempts are rare.

Figure and Data Analysis by Clayton Besaw

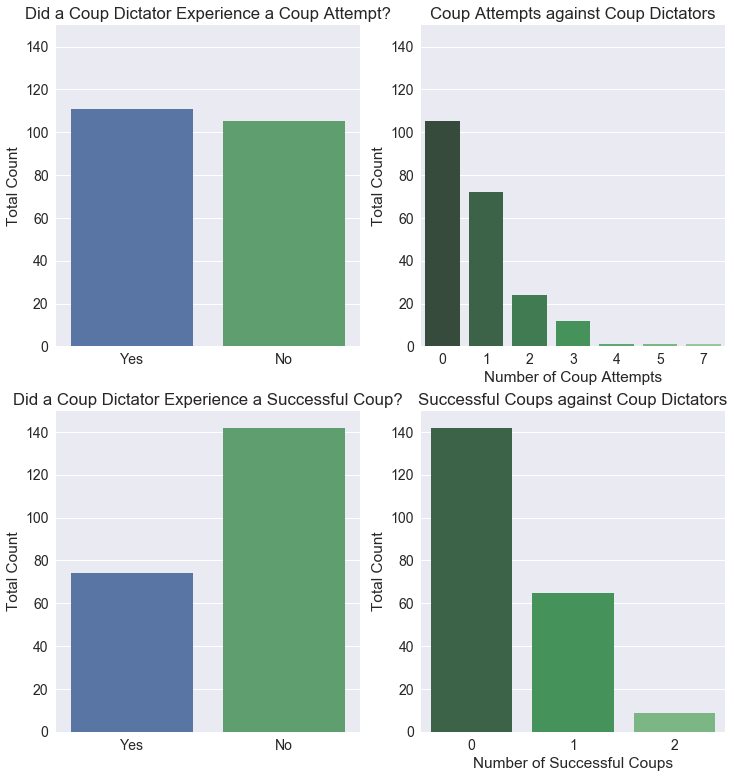

The figure above shows the numbers of coup attempts, successful coups, and successive coups against dictators who came to power via coup in four graphs. Reading from left to right on the top row: a slight majority of dictators who take power by coup are then subjected to a coup themselves. But, there is a steep decline after the first coup attempt, from 72 first coup attempts to 24 second coup attempts, 12 third coup attempts, and only a few fourth, fifth, and sixth coup attempts. Only a small minority of dictators experience multiple coup attempts.

Reading from left to right on the bottom row: only 34 percent of coups against coup dictators are successful. The number of successive, successful coups against coup dictators is low, with only nine such events against coup dictators in our sample.

A dictator who comes to power via coup may likely experience a coup attempt.

Some existing literature supports the idea of a “coup trap” where dictators who come to power via coup face an increased risk of being removed from office by a coup. The descriptive statistics from our REIGN dataset provide support to that idea. Most dictators who come to power by coup may face a coup. However, multiple coup attempts against a single dictator are rare but, as the case of Burkina Faso illustrates, not an impossibility.

Many of these coups are unsuccessful, but dictators can further solidify their power by holding noncompetitive elections. These elections do not deter coup attempts from happening. But a failed coup attempt may deter multiple coups against a coup dictator. All in all, one coup does often lead to another, but many successive coups are rare.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights