Threats by terrorist and militant organizations are becoming increasingly transnational, posing serious challenges to single country-focused UN missions. This fourth blog in our UN Peacekeeping series calls for making peacekeeping less state-centric through local and regional collaboration.

Militant organizations such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State are now collaborating with each other and with transnational criminal networks. They are working together to smuggle weapons, people, and narcotics across national borders. These highly adaptive organizations are also cultivating religious, ethnic, and community-based relationships with populations through a combination of “soft power” tactics. By doing so, they are gaining legitimacy at the local level.

This convergence of security threats presents significant challenges to conventional peacekeeping approaches and practices, which are often narrow in scope and have a single country mandate. These threats also present security challenges that extend beyond the state and are increasingly taking on regional dimensions, necessitating regional peacekeeping responses.

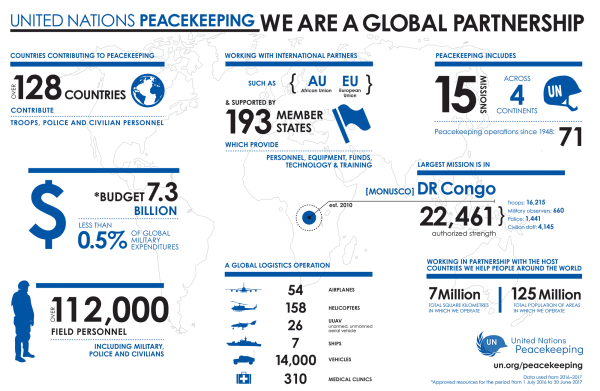

Source: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/infographics?page=1

For example, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) controls northern Mali only through the implicit support of local Tuareg groups. In contrast, peacekeepers have few ties to the local community. This lack of local knowledge undermines peacekeeping efforts: the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is now considered among the most dangerous UN peacekeeping missions ever undertaken, with over 118 peacekeepers killed since it was established in 2013.

Collaboration and coordination by terrorist organizations such as AQIM with other terrorist organizations including Boko Haram in Nigeria, al-Shabab in Somalia, and AQAP in Yemen are common. So too is deployment of experienced combatants across multiple conflict zones. For instance, AQIM fighters are thought to have joined the al-Qaeda insurgencies in Syria and in Iraq in 2013. Sharing strategies and intelligence and facilitating transnational trafficking networks are integral to raising revenue for terrorist organizations. AQIM is also said to be a key player in the highly lucrative cocaine trade across the Western Sahara—estimated to be worth US$900 million in 2011. Other activities include running protection rackets, kidnapping for ransom, and smuggling people, in addition to receiving further transnational funding from governments such as Sudan and Iran.

One possible means of addressing the increasingly transnational threats faced by UN peacekeeping missions would be to further institutionalize cooperation with regional organizations. Currently cooperation of this nature is often ad hoc, occurring only when crises arise. Collaboration between UN missions and regional organizations regarding intelligence gathering, information sharing, border security, illicit funding for armed groups, and potential refugee flows, for example, needs to be built into the planning stages of peacekeeping missions. In the context of MINUSMA, this could entail closer cooperation with the Economic Community of West African States and the African Union. Practically this could include joint security operations against the various armed groups putting down roots across the Sahel.

Only by taking steps to make missions less state-centric can UN peacekeeping begin to effectively address the transnational challenges they face.

Check back next week when we will discuss providing accountability for sexual exploitation and assault in peacekeeping. For previous pieces in this series and other analyses on international conflict and governance, check our ThinkPeace blog.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights