How will the FARC women fit into the very socioeconomic structure they have been fighting against for more than five decades?

The women of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) have come a long way. Their roles and contributions as battle-hardened fighters and lynchpins in rebel camps are as distinct as their new roles in post-war Colombia. They ensured that the 2016 peace agreement contained significant measures of recognition and inclusion of female ex-combatants. But the real fight for acknowledgement has just begun.

In the recently published results of a 2016 study on opinions and attitudes toward Colombian women, more women (79.2%) than men (62.8%) disapproved of the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) being an active political party. This is quite a setback, given that the FARC only recently launched as a political entity in September of 2017; while they are now known as the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria Del Común, or Common Alternative Revolutionary Force, the former guerillas were able to keep their infamous acronym.

The list of statistics reads as a long list of hidden fears and distrust; about half of female respondents (49.5%)—or about four percentage points more than men (45.6%) — do not think the peace agreement will improve security in Colombia. Similarly, more men (59.3%) than women (44%) think that reconciliation between civilians and demobilized FARC guerillas is possible. At the same time, women and men seem to agree that female ex-combatants are far more likely than their male counterparts to successfully transition to civilian life.

These and other statistics are quite revealing. They show, in numerical terms, the deep socio-cultural divide that still seems to hold Colombian society hostage despite the 2016 peace agreement between the government and the guerilla movement. In other words, Colombian society will take some time to come to terms with its violent past. For the women in the FARC, these numbers must be especially daunting given their political aspirations for gender equality in Colombia.

Amid growing insecurity in former FARC territories and political setbacks for the implementation of peace, it is time to revisit some key facts about the FARC women that highlight their agencies—facts that go beyond the coverage of the apparent baby boom, past violations of women’s rights, and past current disapproval rates.

A key question remains unanswered: How will the FARC women fit into the very socioeconomic structure they have been fighting against for more than five decades?

Gender Equality in the FARC

On a research visit to Colombia earlier this year, I interviewed a small group of members of the FARC in the transition zone of La Paz in the northeastern department of Cesar. The level of gender equality among male and female combatants surprised me.

Gaining gender equality in the FARC, however, was no easy feat. It took many years of internal ideological struggle between many of the female recruits and their male counterparts. Eventually, common ground was found through heavy interpretation of Marxism and neo-Marxism’s feminist concepts.

“We at FARC are feminists,” a male fighter told me. He further elaborated on FARC’s extensive history of championing gender parity within its militaristic structure being central to its core ideology of fighting for social equality in Colombia. “Will men forever be the ones calling the shots?” he asked. “What about women? Is their sole purpose to sweep the house, care for the children, and do the laundry?” The obvious answer was “No!” his comrades agreed.

What about women? Is their sole purpose to sweep the house, care for the children, and do the laundry? No.

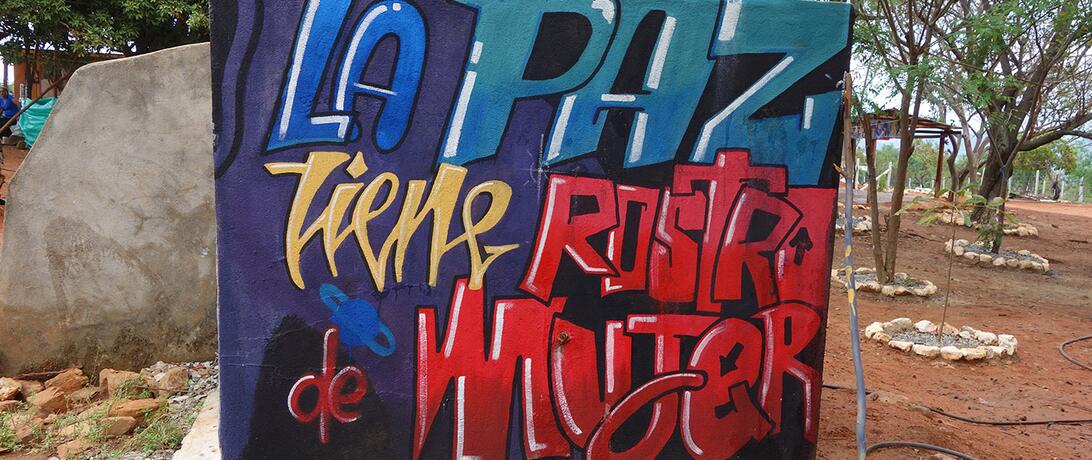

As if to get that point across, the camp brimmed with posters and banners that highlighted the unique roles of the women of the FARC. In speaking to these women directly, it was evident that they not only supported the armed struggle of the FARC, but they also had joined the FARC as a means to realize gender equality.

“We women, we are fighting for equal rights,” a young indigenous woman told me. At a very young age she bore witness to atrocious crimes committed against her community. “The fact that we are here and fighting with … weapons does not mean that we’re not women.” On the contrary, her comrade stressed, “Our fight is the fight of the women who are out there” and who want to pursue this politically.

They want to work in tandem with women in civil society who are already dedicated to changing the gender dynamics in Colombia. It struck me how much these women had thought this through.

“There are reasons to rise up and claim our rights,” the seemingly highest-ranking female fighter said. “We’re going to fight together, us women, and we invite all other women, too.”

On this remote mountain in northeast Colombia, cleared of trees and vegetation and high above the canopy of Colombia’s massive jungle, the women of the FARC have a clear vision for themselves as political actors. It is part and parcel of the FARC’s long-term strategy toward socio-economic justice. And embedded in that cause is the end of women’s oppression.

This strategy of linking gender equality to their Marxist ideology has historically benefited leftist groups by attracting a high number of women. The FARC is no exception.

The support for the armed group cuts across different grievances, needs, and aspirations that are all grounded in a struggle for social justice, most notably land rights and ownership—the genesis of the rebellion that lasted for over five decades.

Violence Against Women in Colombia

It comes as no surprise, then, that much of the criticism voiced by the female FARC fighters in La Paz centered on a Marxist feminist worldview that is firmly ideological in its orientation and juxtaposed against a society where social and economic inequities and exploitation have been institutionalized. A 2012 report conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean by the World Health Organization attests to the high prevalence of physical and sexual violence against women in Colombia.

This pernicious track record of sexual violence inflicted upon indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the late 1990s and early 2000s were abysmal and indicate the continuing and widespread use of rape as a weapon of war. A majority of these cases have gone unpunished to this day.

Given the nature of this fundamental violation of women’s rights, the position the FARC has been claiming as an essentially feminist organization is not that surprising. Many of their female followers are survivors of domestic or sexual violence themselves.

“My parents split up, and I had to stay with my father, and he began to beat me,” one female ex-combatant remembered. “One of the things that I had to witness at home all the time was gender violence … I had to grow up with that.”

The shocking details of many of the stories of FARC fighters are not only indicative of the entrenched conflict in Colombia but of the greater issue of gender inequality itself. They speak to women’s overall lack of empowerment, which the women of the FARC hope to change.

The Added Value of the FARC Women

In a way, the women’s internal struggle for gender equality in FARC set the stage upon which they can advance the role of women beyond the group. The effort to marry their revolutionary struggle to an ongoing gender discourse is not, like critics of the FARC might say, simply a matter of self-adulation. To say that is to deny these women any form of agency. But the opposite is true. These women have a lot to offer. And more importantly, their convictions are an organic outgrowth of a set of shared experiences as both women in Colombia and guerilla fighters.

“I'm not going to be a woman raising children and working hard at home to then have some man telling me that I’m useless, discriminating against me ... No, I won’t have that kind of life,” one female ex-combatant said. She has been with the FARC for over 20 years.

One of her comrades went even further, suggesting that Colombia’s women need to embrace new roles. “Many women in Colombia don’t think beyond the possibility of raising their children. Women need to think far beyond that.”

The Road Ahead

The commitment to women’s inclusion in the Havana peace talks demonstrated a joint determination by both the FARC and the Colombian government to ensure the peace process will be gender sensitive. Now that the FARC is no longer fighting a war as the continuation of politics by other means, to borrow a phrase from Carl von Clausewitz, there is huge untapped potential for the FARC women to advance women’s rights in Colombia more generally. It will remain to be seen how much Colombia’s women will adopt this view over time, as well.

Article Details

Published

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights