Although many Americans may view election violence as a primarily foreign phenomenon, the shooting of Aaron Danielson in Portland resembles episodes of election violence seen around the world. Our longstanding research into global election violence yields many relevant insights for the United States as Americans head into the most contentious election in recent memory. It also provides a warning to political leaders that traffic in unfounded theories of electoral fraud and make appeals to armed groups. Episodes of election violence rarely occur in isolation as they escalate and become rooted into a country’s politics, degrading democratic institutions along the way. This was the case during Reconstruction, and this cycle could take root in the United States again. American political leaders provoking these tensions are playing with dangerous forces they may not fully understand.

Election violence has grown globally; the potential for election violence in the United States needs to be acknowledged.

Bangladesh’s election was just 19 days away when Mohammad Hanif, a local leader of the incumbent Awami League, was killed. Eyewitness accounts painted a grim picture. Hanif was killed by a mob wielding sticks and bladed weapons that supported the rival Bangladesh National Party. By merely attending a political rally, he would be killed by a combination of stabbing and gunshot wounds.

7,000 miles away in Portland, Oregon, and 67 days before the American election, Aaron Danielson was shot dead following clashes between right-wing activists supporting incumbent President Donald Trump and a coalition of left-wing and social justice groups. Both Danielson and his killer on the opposite side of the clashes, Michael Reinoehl, had come to the protest bearing firearms.

Reinoehl argued that his actions were self-defense. Danielson was seeking to defend supporters of his cause that day. In the chaos of the moment, one of them was dead and, less than a week later, so was the other.

Political violence, including election violence, is not exclusive to developing countries. Nor is it novel in the American political experience. Yet, while many would agree that the words “election violence” describe the killing of Hanif, few pundits on either side of the American political divide described Danielson or Reinoehl as perpetrators of election violence.

The insidiousness of election violence, and political violence more broadly, is the ease with which we can accept its normalization.

Many supporters of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party also justify their street clashes and acts of violence as self-defense against an increasingly authoritarian Awami League. Objectively, many of their concerns are merited. However, a cycle of violence has persisted on both sides for decades now. Innocents, entirely unconnected to the original sins of the warring parties, suffer at the hands of a generational political conflict.

Let this serve both as a warning and as an opportunity for the elected leaders of the United States.

Key Findings

Structural Causes

Our research at the One Earth Future Foundation identifies the causes and consequences of election violence in an effort to produce an early warning system for all national elections taking place globally.

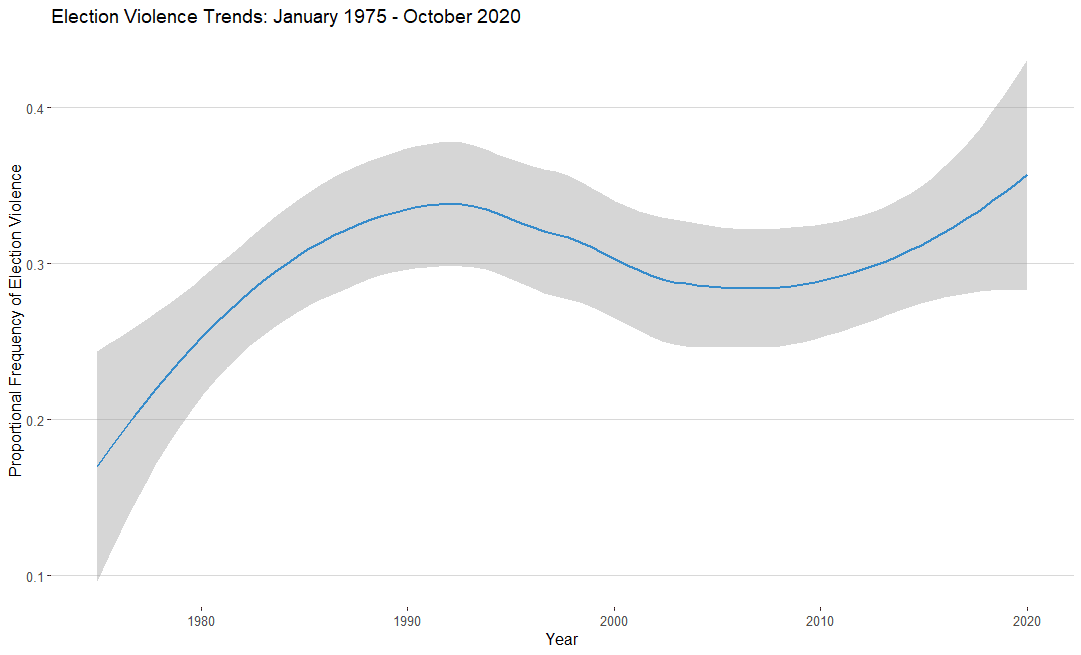

We find that election violence has become increasingly common since 1975. While in 1975, violence occurred in only 14 percent of all elections, as of October 1st 2020 already 42 percent of elections worldwide have experienced violence.

Election violence is multifaceted, involving both psychological causes and intergroup drivers. However, it also involves broader economic, political, and environmental factors that determine the structural context in which electoral politics play out. Because they more easily lend themselves to quantitative analysis, we focus primarily on these structural factors.

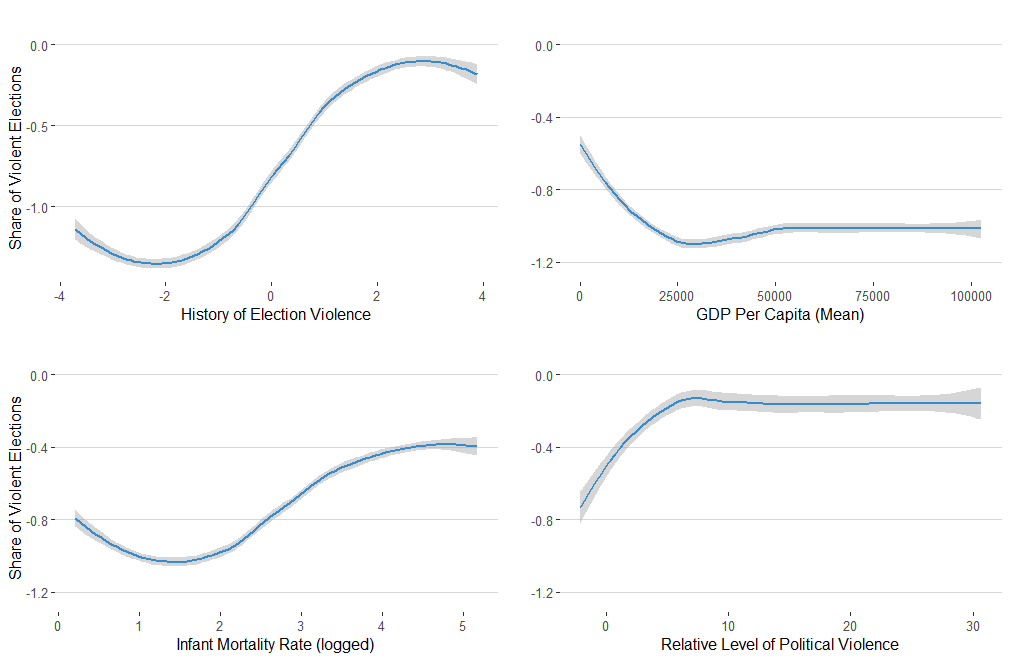

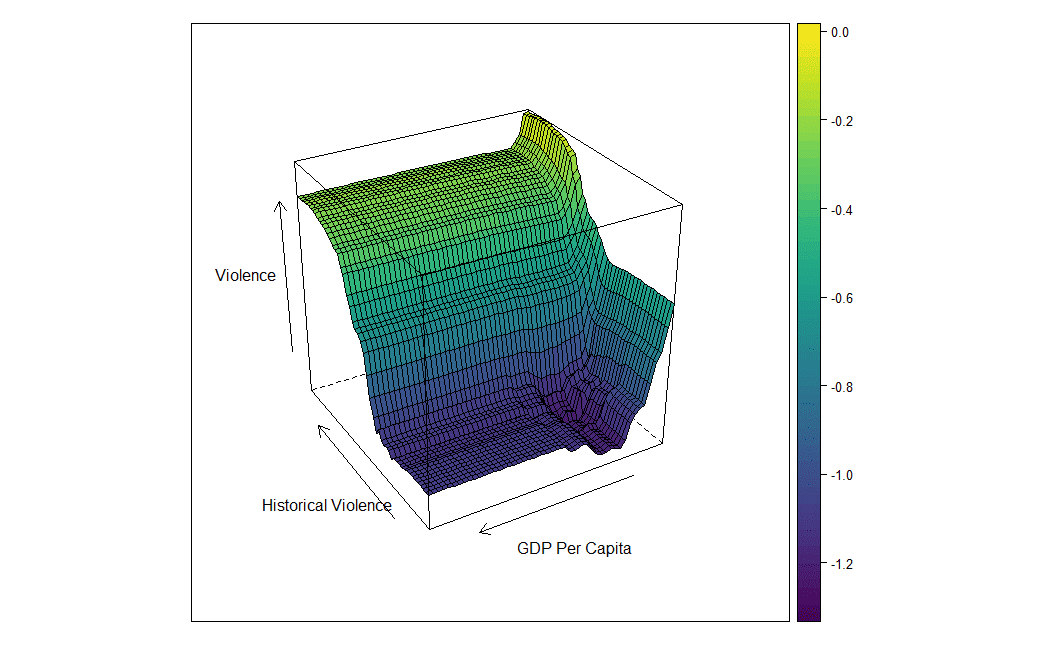

By far, the most consequential structural factor for predicting future election violence is a history of election related violence. Countries that have experienced more election violence more recently run the highest risk of remaining trapped in a cycle of election violence. Political violence attributable to other causes such as civil war or terrorism is also a strong predictor of election violence.

Alongside historical violence, we also find that both GDP and infant mortality rate prove to be the next strongest set of predictors of future election violence.

These factors encapsulate the twin pillars of the structural permissiveness of election violence: the normalization of political violence and weak governmental capacity.

Governments with weak capacity are less able to enforce security and integrity during election seasons. Moreover, when the government is unable to safeguard non-violent mechanisms for the management of conflict between political parties and communities, violence becomes more likely.

This perfect storm of violence normalization and weak governmental capacity makes systematic solutions to preventing election related violence hard to achieve once a country is captured by the cycle.

What about the US?

Based solely on structural factors, our data suggests that the United States only bears a 5% risk of violence on election day, as it does not currently meet the threshold of weak governmental capacity and systematic normalization of political violence.

However, there is reason to believe that our current model is underestimating the risk of election violence in the United States as non-structural drivers of political violence could end up playing an important role in the remaining days before the election.

In particular, we should be aware of our own historical tendency to tolerate political violence and the current trends towards normalizing dehumanizing political speech.

While election violence may seem to many Americans to be a primarily foreign phenomenon, violence surrounding US elections over the past 150 years is historically common.

It was, for example, an important aspect of the consolidation of authoritarianism in the former Confederate states during and after Reconstruction. During this period, white supremacist paramilitary groups carried out campaigns of violence against Black and poor white voters in order to suppress turnout and maintain white supremacist political systems.

The United States in the decades after the Civil War is, of course, fundamentally different from the United States in 2020.

Nevertheless, the residual influence of this historical violence continues to resonate in state legislation and political party behavior that seeks to suppress election participation in minority communities. These efforts have now extended to attempts by the Republican campaign to cast the possibility of electoral loss as only being possible through massive fraud by the Democrats.

These baseless allegations are accompanied by invocations that make use of militaristic linguistic cues, urging supporters to “enlist” into an “army” that will then combat fraud.

This type of elite signaling has already had real-world effects, as evidenced by the group of pro-Trump demonstrators that gathered in front of a polling station in Fairfax, Virginia.

Pro-Trump paramilitary groups have also reacted to these calls, in at least one case because President Trump has directly appealed to them. Were such armed groups to heed the President’s call for poll watchers this would likely significantly increase the risk of spontaneous local violence.

This push towards the re-normalization of political violence is even more precarious given modest evidence that Americans of all beliefs have become increasingly more tolerant of political violence, with this trend being more pronounced for highly ideological individuals.

Although the United States has relatively high government capacity, even a scenario in which minor localized violence occurs could spark a cycle in which armed perpetrators seek to build on increasing elite and non-elite support for the role of political violence.

These cycles can have deleterious effects for democracy overall. Violence can undermine the popular legitimacy of elections and create a situation where electoral outcomes are primarily viewed as the prize for violently overwhelming your political opponents. Meanwhile, government capacity can also suffer as institutions become more politicized and tied to violence.

There is therefore a clear imperative for action to prevent such a cycle from beginning in the first place.

Law enforcement has an important role to play in this regard by proactively working to thwart violent plots and respond to spontaneous violence. Likewise, Democratic politicians and social leaders also have a role to play in countering the President’s signaling by advocating and demonstrating non-violent alternatives to resolving political grievances.

However, these actions cannot be expected to prevent all instances of violence.

America’s best chance to avoid falling into a cycle of election violence lies in reestablishing the legitimacy of elections and their centrality to democracy. If voters are brought to believe that the electoral process is fundamentally flawed, it should be no surprise that some will come to see violence as a justifiable alternative to traditional political participation, even if such beliefs have no basis in reality.

In the end, this burden largely falls on the President and his subordinates, even as they promote false theories of election fraud.

As Above, So Below. Democracy is worth protecting

To political leaders that care about the physical integrity of electoral politics, the warning is now clear. Do not equivocate and do not play with fire for political gain. Do not eschew effective government solutions either.

The Faustian bargain being made between political leaders and their extremist support will one day exact a cost on our democracy. If our government is unwilling to use its capacity to safeguard the promises of the U.S. Constitution, the further normalization of political violence will undercut the legitimacy and efficacy of our democratic institutions, especially as foreign adversaries seek to push us further down this path.

The nation does not suffer from a lack of resources, capabilities or human capital. It suffers from a lack of courage from political leaders, at best, and willful promotion of violence at worst.

President Lincoln presaged this precipice in his Lyceum address.

Lincoln argued that violent politics is a direct threat to the continuation of our democratic institutions, that the greatest threat to our Constitution would not be foreign enemies, but ourselves.

When election violence takes root, what then is to stand in the way of ambitious politicians who would answer first to their armed supporters and not the law of the land?

Allowing a slow building cycle of election violence to take root would condemn future generations to decades of grief and misery for the simple inalienable right to make one’s voice heard. It would further weaken our democracy and cast a shadow on the global project to help those that would seek to escape from the oppression of election violence and authoritarian overreach