Elections can serve a catalyst for coups and other forms of political violence. Take a look at OEF Research’s CoupCast for continued, in-depth analysis of the drivers of coup risk around the world.

This is the final post in a five-part, weekly series on elections in dictatorships. Visit our CoupCast site for information about our REIGN database and previous commentary on coups d’état.

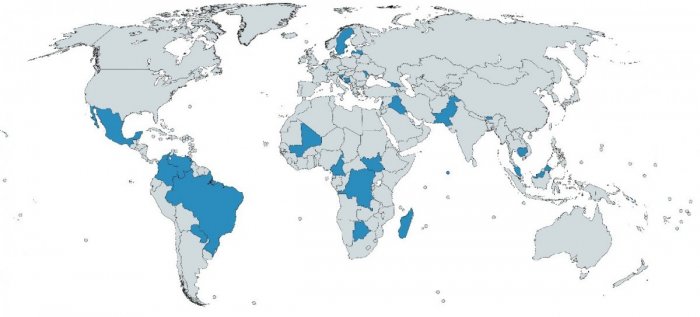

As the last installment in our series on elections and dictatorships, we look forward to what the rest of 2018 has in store. The map below highlights the 26 countries (in blue) that will experience an election in the remainder of this year.

Countries with Head of State Elections the Remainder of 2018

The states holding these elections vary widely from well-established multiparty democracies to one-party states. Other than the recent election in Egypt, the remaining elections in 2018 do not neatly fit within the dynamics discussed in the previous posts of this series. However, the risk of coup world-wide is still apparent. In fact, 2007 was the only coup free year since the First World War, suggesting that a coup is more likely than not to take place.

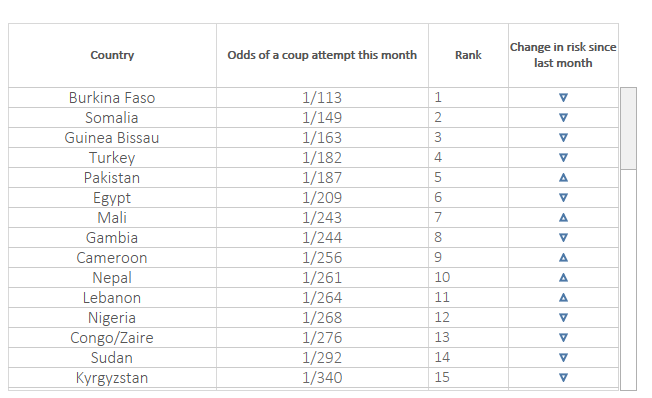

Below is the current (April 2018) ranking of countries by coup risk as measured by the CoupCast model. Some of the countries, like Burkina Faso (here) and Egypt (here and here), have been discussed in previous posts in this series.

Coup Risk by Country, by Month

What are some of the other political dynamics in countries with a risk of coup?

The upcoming elections in Mali, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Venezuela are highlighted below because of their history of coups and the potential for their election delays to increase coup risk.

Mali

Polls, originally scheduled for December, will take place between April and July. President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK) will face reelection amidst considerable discontent over the lack of progress made in his first term. In the most recent iteration of our CoupCast model, Mali has the eighth highest risk of coup. IBK’s position is not as strong as one would expect of an incumbent, but the upcoming election could boost his legitimacy and strengthen his mandate. The Malian military has shown a willingness to undertake coups; most recently in 2012. If they were to intervene again, they would very likely do so before elections take place and IBK has the opportunity to legitimate his leadership.

Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

The DRC’s long-awaited elections may finally happen at the end of 2018, a full two years after President Joseph Kabila’s constitutional mandate expired in December 2016. Although Kabila promised to stop-down, there have been a series of postponements blamed on logistical and financial challenges. Several attempts to broker a compromise between Kabila’s government and the fragmented opposition have produced no results. The government is actively undermining and repressing any real electoral challengers. Kabila seems to have mitigated the risk of coup by centralizing control of the most elite sections of the military, but a coup by members of the military which seek to take power before a new, elected leader can be established is still a threat. The election is also likely to trigger broader political violence. Previous delays have resulted in protests and violent repression, a pattern that is likely to repeat itself if election preparations are delayed again or viewed as unfair to the opposition. What’s more, the ongoing national level political crisis has created a narrative which help fuel the DRC’s patchwork of previously localized conflicts.

Venezuela

Incumbent President Nicolas Maduro has faced a growing protest movement as the country’s situation worsens. The ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) is doubling down by targeting both the state’s institutions, as well as individual opposition leaders. In reaction, opposition parties are choosing to boycott the election. As the May elections grow nearer there is an increased risk of renewed protests and subsequent state violence. There appears to be some degree of dissent within the Venezuelan armed forces about their role in society and continued support of Maduro. As demonstrated in previous posts in this series, the risk of coup rises significantly before nondemocratic elections such as this, but falls dramatically after. If the Venezuelan armed forces were to choose to take things into their own hands, they would be most likely to do so before the election. After that point, Maduro faces a significantly lesser risk of coup.

Will 2018 be a coup-free year?

Elections are inflection points in states around the world. In some cases, this can mean they serve a catalyst for coups attempts and other forms of political violence. Take a closer look at OEF Research’s CoupCast project for continued, in-depth analysis of the drivers of coup risk around the world.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights