In our first post in a new series on elections in dictatorships, we discuss the first presidential election to take place in Egypt for the first time since 2014 and the strategies of hosting elections, even noncompetitive ones, for dictators by coup.

This is the first post in a five-part, weekly series on elections in dictatorships. Visit our CoupCast site for information about our REIGN database and previous commentary on coups d’état.

Presidential elections in Egypt will take place this week for the first time since 2014. While the race officially has two contenders, the outcome of the election is a certainty. Sitting president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is expected to win despite massive economic inflation and a range of human rights abuses. Mostafa Mousa of the Ghad Party, the only other candidate running in the election, is largely seen as a puppet of the al-Sisi regime.

The conditions are ripe in Egypt for al-Sisi to remain in power. How did Egypt, once the beacon of the Arab Spring, get here?

Al-Sisi came to power in 2013 after orchestrating a coup d’état against elected leader Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. Al-Sisi’s tenacity for violent repression was made immediately clear in the following months. Between July and August 2013, the Egyptian police and army opened fire on crowds of demonstrators, with the deadliest incident causing nearly 1,000 deaths in Rab’a al-Adawiya.

Yet, al-Sisi hosted and won the 2014 presidential election in Egypt with 97 percent of the vote. In the four years since, he banned the Muslim Brotherhood and promised that the 2011 Tahrir Square demonstrations would never happen again. Police reportedly raided more than 5,000 homes and arrested hundreds of activists ahead of the anniversary of Tahrir Square in 2016.

He has followed up on these promises with widespread suppression of civil society. In November 2016, the regime passed a widely condemned bill that bans NGOs from activities the government deems to “harm national security” and that places strict restrictions on domestic and international funding for local NGOs.

Several opposition groups put forward candidates to run against al-Sisi. They all backed out, facing intimidation and arrest. As a result, these opposition groups are encouraging voters to boycott the presidential elections.

If the al-Sisi regime is controlling the outcome of the presidential election, why bother to host an election at all?

Hosting noncompetitive elections in a dictatorship is one strategy to stay in power. This might be a particularly useful strategy if a dictator took power via a coup. Our CoupCast program uses the unique REIGN dataset to forecast the risk of coup in every country, every month. From these historical data, we can glean a better understanding of why coups happen and why elections happen in dictatorships.

Considering that al-Sisi came to power after orchestrating a coup, how long on average does a dictator by coup remain in power?

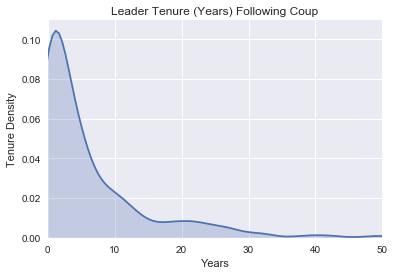

Our historical data show that the majority of leaders who come to power via a coup experience a tenure up to 16 years following a coup, with the average at 6.1 years and the median at 2.9 years. One leader, Fidel Castro, remained in power for 49.1 years following a coup. Whether or not they host elections may be a key element accounting for this variation.

Our historical data show that the majority of leaders who come to power via a coup experience a tenure up to 16 years following a coup, with the average at 6.1 years and the median at 2.9 years. One leader, Fidel Castro, remained in power for 49.1 years following a coup. Whether or not they host elections may be a key element accounting for this variation.

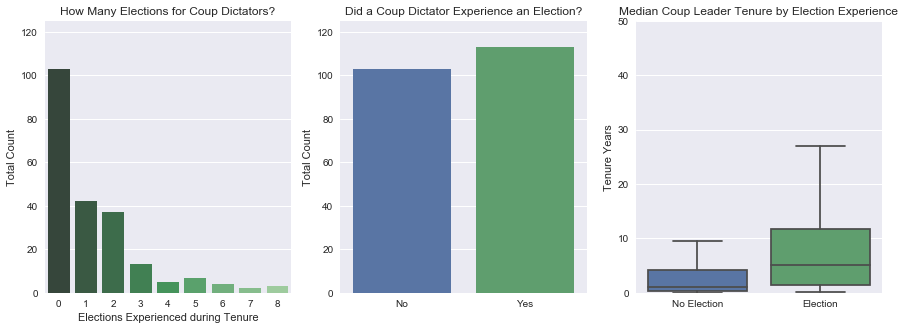

How frequently do dictators by coup host elections?

Figures and Data Analysis by Clayton Besaw

The first and second figures show us that most dictators by coup (at 52 percent) tend to hold at least one election. The third figure is particularly important. When dictators by coup do not host elections, they stay in power for 3.4 years. When they do host elections, they stay in power for 8.5 years.

Dictators by coup who host at least one election stay in power longer than dictators by coup who do not host elections.

Hosting elections, even noncompetitive elections, appears to be a good strategy for dictators by coup who want to stay in power longer. But, this is still a risky decision as dictators expose themselves to competition and public scrutiny during elections. According to our CoupCast projections, Egypt is the second most likely country to experience a coup this month.

How can hosting elections be both a good strategy for staying in power and a risk for dictators by coup?

The political dynamics in dictatorships are complex. This is particularly true for those who gain power through coups. As a rare event, it is hard to say with certainty that a coup will take place. By drawing on our REIGN data and examining historical cases of coup attempts and elections in dictatorships, we can reveal general lessons.

This is the first post in a five-part, weekly series examining the role of elections in dictatorships, particularly focused on dictators who take power by coup. In subsequent posts, we’ll discuss the following questions: Are coups more likely before or after elections? Do coup leaders face a higher risk of a coup attempt? Do dictators by coup ever lose elections? If they do, do they step down?

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights