* The article was originally published on ONN's Datayo platform.

The early morning of May 27, 1960 marked a major turning point in Turkish civil-military relations, as well as the country's history in general. Around 3 a.m., two relatively small groups of junior officers, one in Istanbul and one in Ankara began taking over key government offices and communications hubs, arresting senior government and military officials loyal to the incumbent Democratic Party (DP) government.

Although the putschists were quickly able to achieve their objectives and announced the toppling of the DP government, the outcome was far from certain at the time. The Istanbul group completed its objectives before the Ankara group and was initially unable to get in touch with its partners, unsure whether the latter group had been foiled or had decided to betray the Istanbul plotters.

However, they were not alone in their anxiety. A year earlier the United States had begun deploying nuclear weapons to Turkey, which included both gravity bombs and the nuclear-tipped Honest John missiles. A memorandum from the congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE), written in December 1960, asserts that the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, General Lauris Norstad, was so concerned by instability in Turkey that on two occasions he almost ordered the evacuation of these weapons.

Though General Norstad would later respond to these assertions by seeming to claim that JCAE staffers had misinterpreted the "routine" review of contingency plans for evacuating US nuclear weapons from the country (and that he himself had not even been aware of such reviews), similar concerns were raised after the US imposed an arms embargo on Turkey following Turkey's invasion of Cyprus. As Turkey responded by closing US bases in the country (leaving US personnel and equipment stationed at NATO bases), Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger expressed concerns about the security of US nuclear weapons, noting their vulnerability as the US only had a "small guard" in the country.

The resulting war between Turkey and Greece, both of which hosted American nuclear weapons through NATO, contributed to the decision to draw down deployed US nuclear weapons in Europe and the introduction of greater security measures. The end of the Cold War saw an even more precipitous drop in deployed nuclear weapons in Europe while in Turkey there are now only roughly 50 gravity bombs.

Concerns about the security of the nuclear weapons remaining in Turkey have persisted, particularly following the ill-fated July 2016 coup attempt in which the plotters utilized the very same base where these weapons are stored, Incirlik Air Base. This concern has heightened in the context of a broader estrangement between the US and Turkey, driven principally by American cooperation with Kurdish militias in northern Syria and Turkey's procurement of the Russian S-400 air defense system.

In the wake of the Turkish invasion of northern Syria in October 2019, during which Turkish forces fired artillery at American special forces, the New York Times reported that American officials were reviewing plans to evacuate US nuclear weapons from Turkey.

Turkey's relationships within NATO have also begun to sour significantly. For instance, heightened tensions with Greece over maritime claims in the Eastern Mediterranean have escalated over the past year, while Turkey and France have found themselves supporting rival factions in the Libyan civil war. These issues, among others, boiled over at a recent NATO summit, with Turkey becoming increasingly estranged from fellow alliance members.

While the events driving Turkey's deteriorating relationships with NATO and the US are fairly visible, the continued risk of political instability is perhaps more opaque.

Here we shed some light on the latter by providing some background on Turkish civil-military relations and by offering estimates of the risk of a coup risk based on our coup forecasting model, CoupCast, which uses historical data on structural economic, political and environmental factors to estimate the risk of coup that countries face in a given month.

Turkish Civil-Military Relations in Brief

The Turkish military has often been characterized as one of several militaries in the Middle East and North Africa that have historically been able to "rule without governing." In popular understanding this is often understood to mean that they have effectively defined the boundaries for politics without typically dictating directly what can happen within those parameters.

In the Turkish context, this has popularly been understood to mean that the military has acted as the vanguard for a secular, modernist political order inspired by the first generation of military officers that founded the Turkish Republic in 1923 following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Military support for this ideological position was certainly widespread during the first several decades of the Turkish state, during which time the Republican People's Party (CHP) ruled while commanding almost complete loyalty from the military.

However, recent scholarship has added significant nuance to the image of the Turkish military intervening in uniform support of a secular civilian political order. Ideological and political differences among officers in the military often shaped the manner and extent of military intervention, with groups in the military even allying themselves with civilians in efforts to tame interventionism.

Indeed, political differences between senior and junior officers in the Turkish military were at the center of the two unsuccessful coups in 1962 and 1963, both of which were led by Colonel Talat Aydemir. The military was split between those more senior officers who favored a more rapid return to civilian rule following the 1960 coup referred to above and a group of more junior officers that favored a prolonged military rule in order to introduce wide-ranging reforms that would "usher in the 'Second Republican Regime'." In the lead up to the 1962 coup, senior officers attempted to ensure a successful transition to civilian rule by taming interventionist elements of the military through purges and the creation of government bodies such as the National Security Council that would ensure military involvement in government decision-making.

Although both coups failed, and Colonel Aydemir was executed after the second failed attempt, these episodes paint the picture not of a unitary actor dedicated to controlling a country's politics but rather a deeply divided organization struggling to manage internal dissent. In other words, the military was confronting issues common to large bureaucracies, albeit with higher stakes than those at your local DMV.

The above popular understanding of Turkish civil-military relations also implies that the military is the actor driving politics and the civilian government largely implements decisions in keeping with the military's vision. However, the relative positions of the military and the civilian government have shifted over time. Indeed, civil-military reforms taken earlier under Recep Tayyip Erdogan's rule had inspired a sense that perhaps the military's days of guardianship were behind them.

Applying a principal-agent framework of civil-military relations, [1] further research has shown that, in Turkey, the military has acted both as the principal (an actor who delegates authority) and the agent (an actor to whom authority is delegated) across time, which has also affected the degree and manner of praetorianism.

For instance, from the Republic of Turkey's founding through 1960, the military did view itself as a guardian of secular modernism but largely refrained from intervening in politics (although this was also partly because so many members of the ruling CHP were former military officers). As such, the tutelary status of the military during this period was mostly symbolic, with the military acting as a loyal agent of the civilian government.

Following the 1960 coup, however, the military exercised much greater oversight of civilian rule, flipping the past arrangement on its head and becoming the principal and relegating the civilian government to an agent status. One exception to that general trend was during Turgut Ozal's presidency when Ozal was able to exercise a greater degree of autonomy, even in the area of foreign and defense policy during the First Gulf War. This period is characterized by a "tug of war" over the status of principal.

The civilian government regained its principal status in the early 2000's, initially through the institution of various civil-military reforms aimed at achieving Turkey's admission to the European Union. However, further actions taken by then-Prime Minister Erdogan and his then-allies within Fetulah Gulen's Islamist movement to install loyalists within the military as a coup-proofing strategy planted the seeds of further intra-military divisions that would eventually lead to the July 2016 coup. After Erdogan's alliance with Gulen's movement came to a bitter end in 2013, Erdogan endeavored to remove all Gulenist officers from the military which, in turn, incentivized these Gulenist officers and their allies to attempt to overthrow Erdogan before they could be purged.

Despite movement towards a principal-agent framework in which the civilian government was able to exercise greater oversight of the military, political divisions were able to take hold within the military and provoke an episode of what would be termed, using the language from principal-agent literature, an extreme form of shirking. As such, views that the military is either an all-controlling political actor or that the civilian government has completely tamed the military both fall short. Rather, the level of praetorianism is a "dynamic, continuous variable," albeit one that is extremely difficult to measure.

Seen through this lens, Turkish civil-military relations have been dynamic and have undergone both rapid and gradual transformations. Moreover, positive civil-military reforms have proven inadequate to prevent the politicization of the military or the subsequent political divisions within the military that have foreshadowed coup events. While foreseeing such political divisions and the level of the military's praetorianism is nearly impossible, we can estimate the structural permissiveness of coups using our CoupCast forecasting model.

Turkey's Structural Risk of Coup

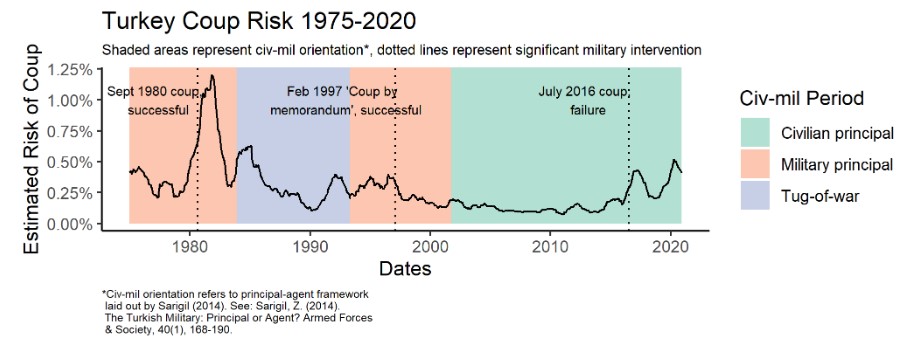

Turning our attention to CoupCast’s view of Turkey's coup risk, we can see that after a fairly significant spike in coup risk following the country's September 1980 coup, risk gradually decreased and flattened out, especially after the switch from military principal to civilian principal.

However, coup risk spiked in the lead up to the 2016 coup and continued a steep, upward trend afterwards. While this risk began to decrease after September 2016, it again reached a peak in late 2019 before beginning another decline (still reflecting, however, a general upward trend in the country's risk of coup).

Displaying these trends in risk over the country's different civil-military periods, we can see that the civilian government regaining its principal status foresaw a general decline in and stabilization of the country's risk of coup in the 2000's that ended roughly around 2010. Since then, coup risk has been following an upward linear trend despite fluctuations that have reached local minimums in mid-2018 and in December 2020.

Overall, this suggests a generally negative trend and that the country is becoming a more fertile ground for military coup. However, for our purposes, an important question is whether this trend will continue beyond 2020. To help answer this, we can look at what specific factors are influencing Turkey's risk of coup.

Here we examine the variables which are most important for coup prediction and for which Turkey has a significantly higher/lower value for December 2020. Those variables are:

-

The time since most recent coup attempt

-

Duration of regime type

-

Level of internal political violence

-

Duration of the incumbent leader's tenure

-

Change in the average tenure of leaders in the region

-

Change in regional economic growth

-

Average level of conflict in the region

-

Change in regional GDP

-

Average level of economic growth in the region

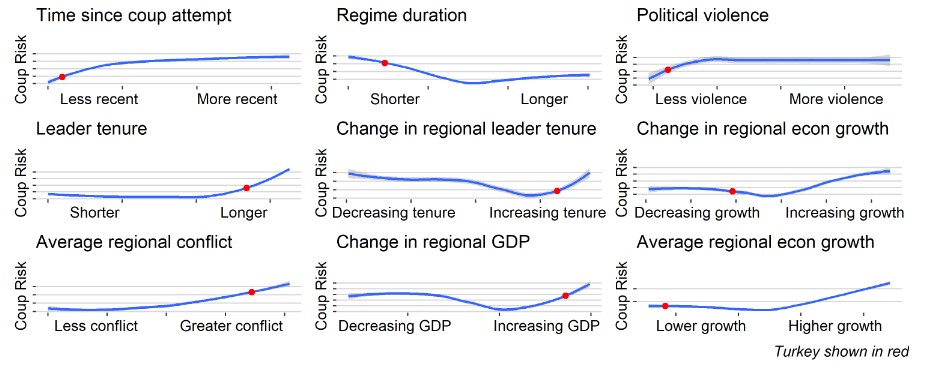

Below we display nine different plots that demonstrate how coup risk is impacted by these individual factors. Turkey's December 2020 values for each variable are shown in red in order to give a sense of which predictors may be specifically influencing Turkey's current estimated coup risk.

Here we see a mixed bag. Turkey's 2016 coup occurred relatively recently, but the plot above suggests that the longer the country goes without another coup, the less this particular factor will increase coup risk. Likewise, Turkey's regime type is fairly new, as our data ceased to categorize it as a democracy in May 2019. While our plot above suggests that newer regimes will tend to be at greater risk of coup, as time goes on the increase in risk due to this factor should also decrease.

However, turning our attention to political violence within Turkey and to regional conflict, we see some potentially less optimistic trends. Political violence within Turkey has had several spikes within the last several years, primarily driven by the continued conflict between the Turkish Government and the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which is itself connected withTurkey's fight against the People's Protection Units (YPG) in neighboring Syria.

Meanwhile, conflict within the broader Middle East and North Asia (MENA) region remains high in several countries and shows little sign of decreasing. Indeed, Turkey itself has been participating in a number of these conflicts, including in Syria and in Libya, while it has also carried out strikes against PKK targets in Iraq. Taken together, it would appear that both predictors related to violence and conflict would either maintain Turkey's risk of coup or increase it into the future.

Regional economic indicators are also a somewhat mixed bag as the monthly change in regional GDP has been positive, although this is largely driven by only a few countries, namely Israel, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Meanwhile, average economic growth as a percentage of GDP is rather low at the regional level and has also slightly decreased.

Finally, leader tenure shows a steep upward curve as tenure increases, while the current value of change in average regional leader tenure is also on an upward slope. The latter will likely continue to increase given the large number of autocratic leaders in the MENA region, although relatively recent changes in leadership in Iraq, Lebanon and Kuwait may mediate this.

However, as Erdogan continues his tenure in power above graphs would suggest that risk of a coup in Turkey will increase. Notably, leader tenure has among the steepest curves of all our plots shown above, suggesting its effects on coup risk could be especially pronounced.

This may prove significant as Erdogan could be in power quite a long time. Although the 2023 elections are still years away, defeating him electorally will likely prove quite challenging for the opposition as Erdogan remains the most popular politician in the country. This is despite economic growth plummeting and the Turkish lira bleeding value through the majority of this year.

Moreover, the AKP and their coalition partners the Nationalists Movement Party (MHP) have been successful in fending off concerted efforts by the opposition parties to call early elections in the midst of unfavorable conditions for the incumbents.

Short of electoral defeat, it is unclear what could lead to Erdogan's exit from politics, especially as he has no clear successor.

The aforementioned economic issues have led to Erdogan dismissing his finance minister and son-in-law Berat Albayrak who had most often been discussed as Erdogan's potential successor. While there are other potential heirs in Erdogan's orbit, such as interior minister Suleyman Soylu, part of the reason the question of succession is so unclear is that Erdogan himself has personalized the AKP to a very large extent, meaning the very future of the party is in question in his absence.

How Much Risk is Too Much?

Overall, our examination of Turkey's historic civil-military relations and estimated coup risk paint a somewhat pessimistic picture for political stability in the short term, although this becomes significantly less certain as the time horizon increases.

Nevertheless, the estimated risk of a coup in Turkey is increasing on the eve of a new American presidential administration taking office that appears poised to take a harder line on US-Turkish issues. President-elect Joe Biden has in the past called Erdogan an "autocrat" and stated that the US should be supporting Turkish opposition parties. Moreover, on December 14 the Trump Administration imposed sanctions on Turkey under the Combatting America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in response to Turkey's purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense system, something the Trump Administration had resisted doing until now. While US-Turkish relations have been bad for some time, it seems likely they will continue declining in the near term.

What does this all mean for the safety and security of US nuclear weapons in Turkey?

To begin with, even if a coup were to occur, which itself is far from certain, much would have to go wrong for nuclear weapons to be compromised. The weapons are guarded by American forces, stored in vaults, and equipped with devices meant to prevent their unauthorized use (although these do not work indefinitely).

Moreover, it is unclear what the motivation for seizing the weapons in the context of a coup would be, although one could imagine nightmare scenarios in which conflict could erupt between American and Turkish forces in the event of a coup attempt given the widespread belief of American involvement in the 2016 coup. On the other hand, plotters again using Incirlik Airbase could attempt to seize the weapons in order to use them as bargaining chips.

However, even while acknowledging the low likelihood of such nightmare scenarios, the standard for nuclear safety and security should not be that a worst-case scenario is unlikely if something goes wrong. Rather, the standard should be that something going wrong in the first place should be exceedingly unlikely.

The problem is not that there are insufficient safeguards to protect against the seizure and potential usage of U.S. nuclear weapons, the problem is that these measures are relied upon in lieu of broader efforts to eliminate the possibility they would need to be used. None of these measures are ironclad and can only ever serve to mitigate risk, while their ability to mitigate risk to an acceptable level is mostly a function of what that initial level of risk is.

In the case of Turkey, uncertainty regarding the country's political stability and the contentious relationship with the U.S. put this initial level of risk too high.

Put another way, if you have to worry whether or not a permissive action link (the device on nuclear weapons that prevent unauthorized use) will stop someone from using a nuclear weapon seized in the chaos of a coup, then you are accepting too much risk in the first place. Such safeguards should protect against unforeseeable events and push overall risk as close to zero as possible.

The Biden Administration will have a wide range of Turkey-related issues with which to deal, such as how to leverage CAATSA sanctions to convince Turkey to give up the S-400 system and how to repair relations between Turkey and other NATO members. It should also take the opportunity to remove the US nuclear weapons stored in Turkey as part of a recognition that their safety and security cannot be guaranteed to acceptable levels.

[1] A principal-agent relationship is treated as a strategic relationship in which the principal procures an agent to carry out a specific set of tasks. The principal is assumed to want the most work for the least cost while the agent wants the most pay-off for the least amount of work. Divergences of preferences and interests can lead to "shirking" by the agent, requiring the principal to instate oversight and punishment mechanisms. In the civil-military context, coups would be the most extreme form of shirking. See: Feaver, P., Armed Servants: Agency, Oversight and Civil-Military Relations, Harvard University Press, 2003